Vasse House

by Joshua Duncan, introduction by Billy McQueenie

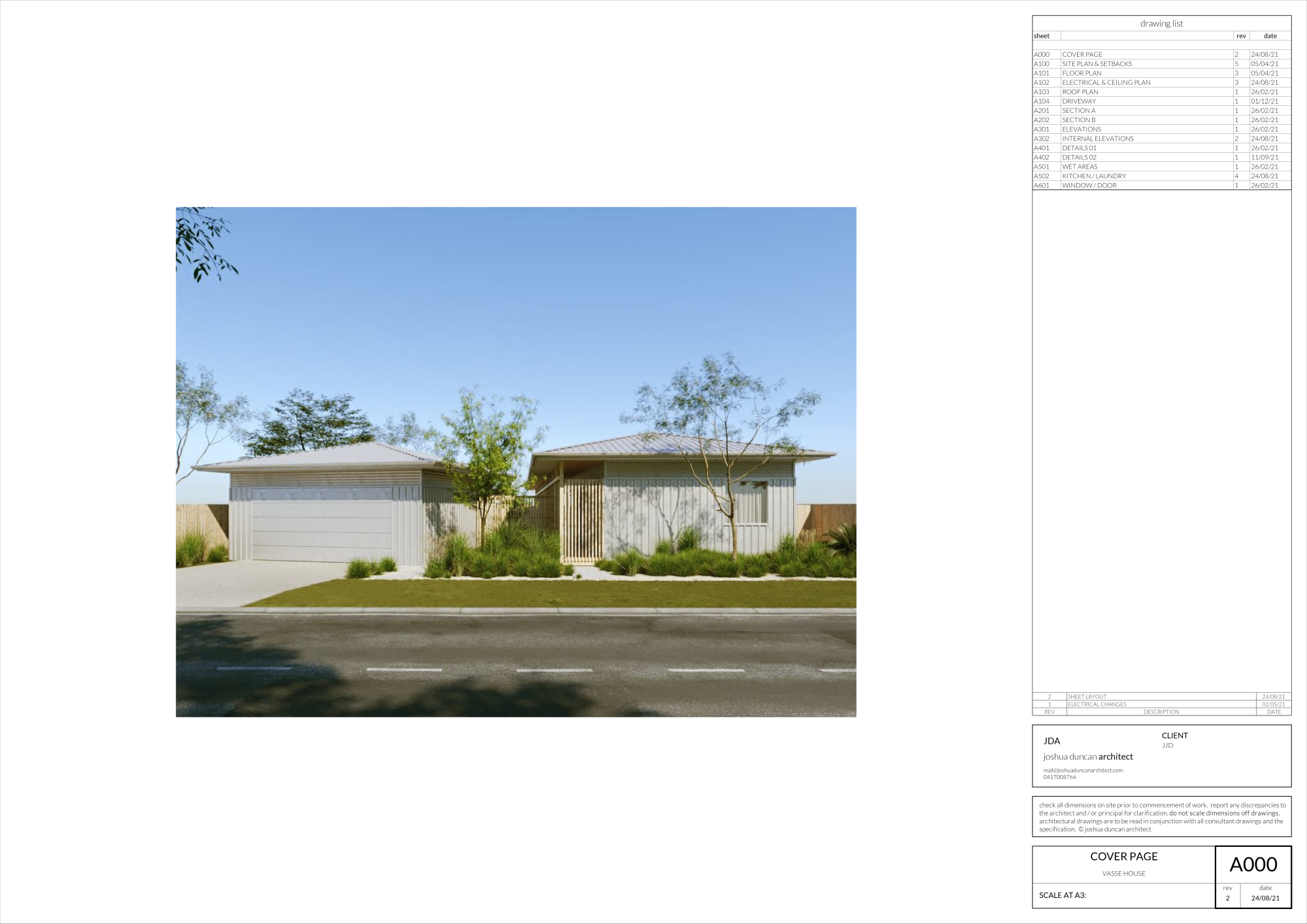

In a sandy suburban development, a few hours south of Perth, sits what appears to be two common garden sheds. Each topped with a hip roof and covered all over with metal cladding, the pavilions reveal little to the street. Only on closer inspection, maybe after a double take, would you notice the telltale signs of suburban life: a small red letterbox, a camping chair, some bamboo blinds shading a long deck. Hiding in plain sight, the two garden sheds are actually one of Australia’s best new houses.

Vasse House by Joshua Duncan is in Kealy, WA.1 New suburban developments like Kealy have long been maligned in architectural circles. The wide streets and mountable kerbs spread through what were once rural estates, populating them with lowset double brick houses. The closed, insular dwellings often cover over 75% of their site area, filling the lots with two-car driveways, rumpus rooms, master suites and al fresco dining areas. The suburbs have become emblematic of the environmentally irresponsible building practices of Australian domesticity. It is pertinent, then, to note that the Vasse House adheres to the rules of its context—while quietly undermining all of them.

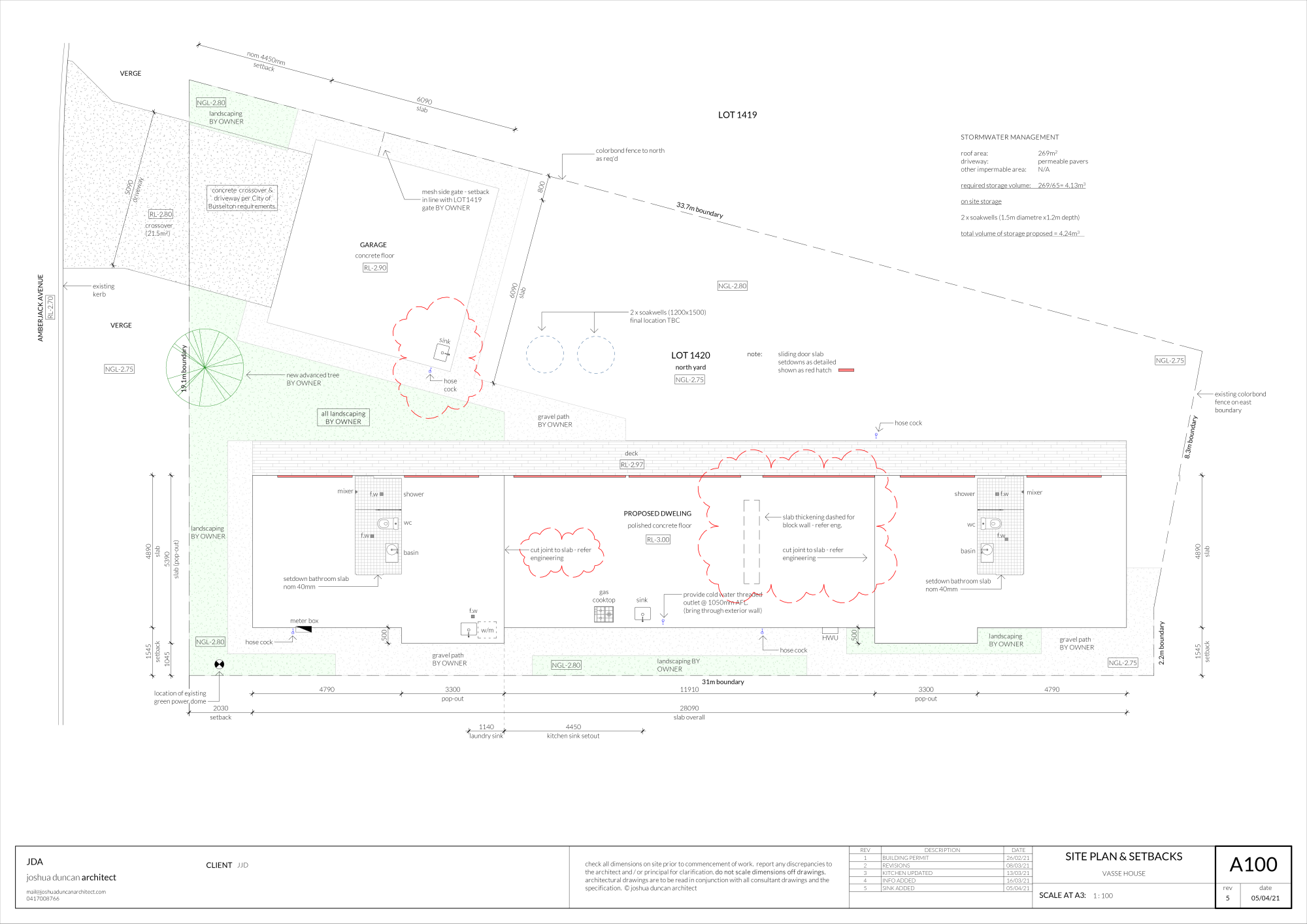

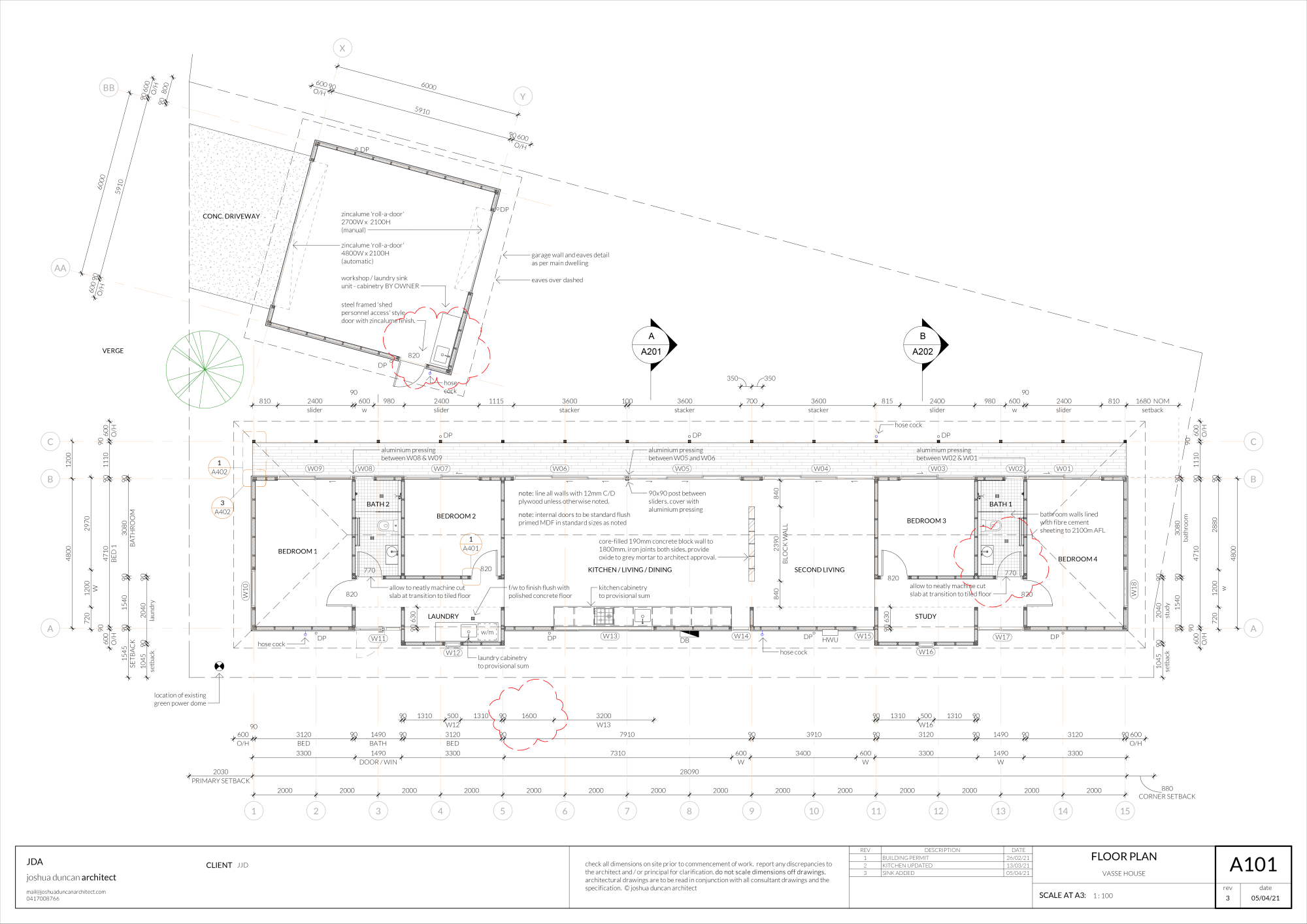

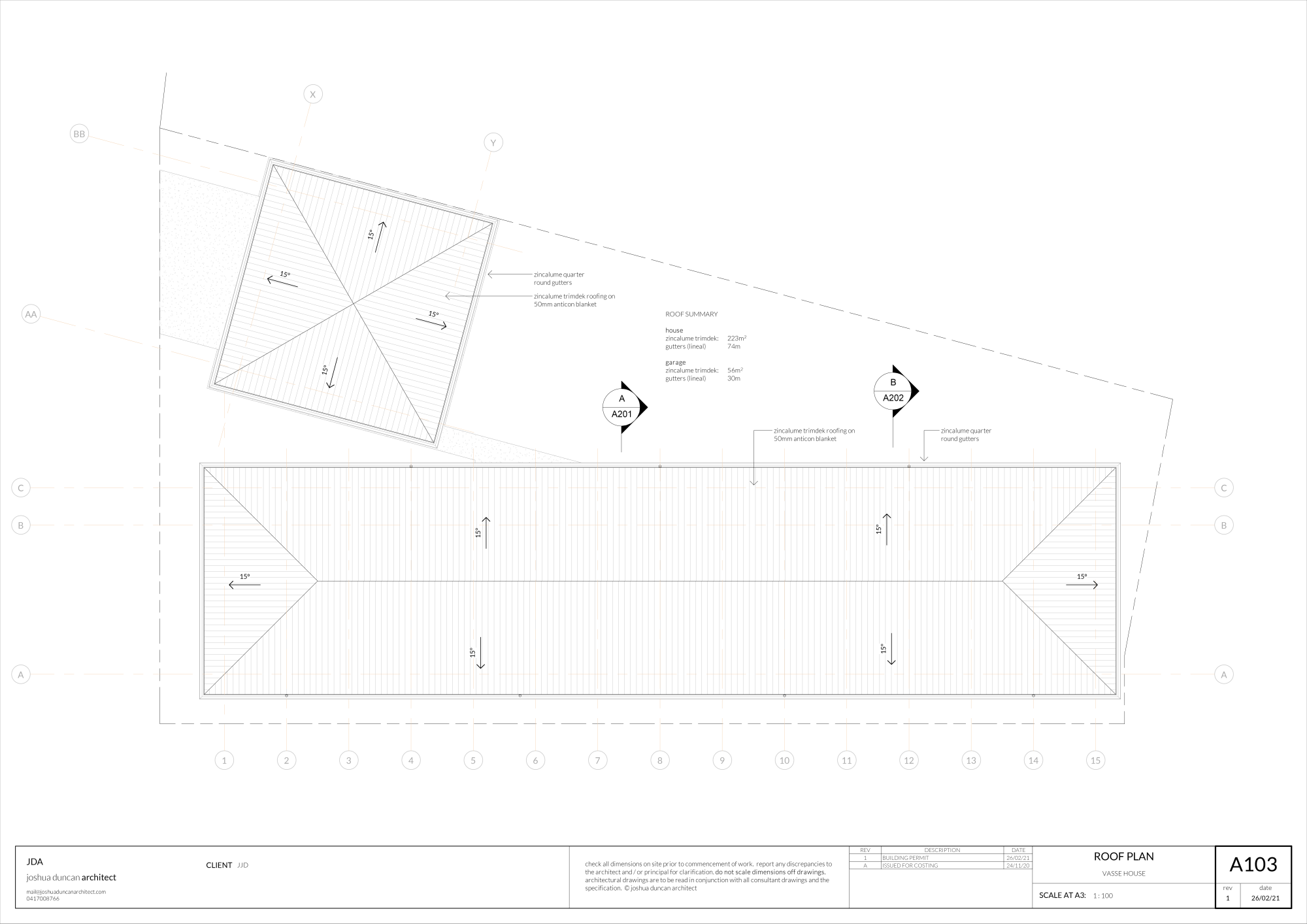

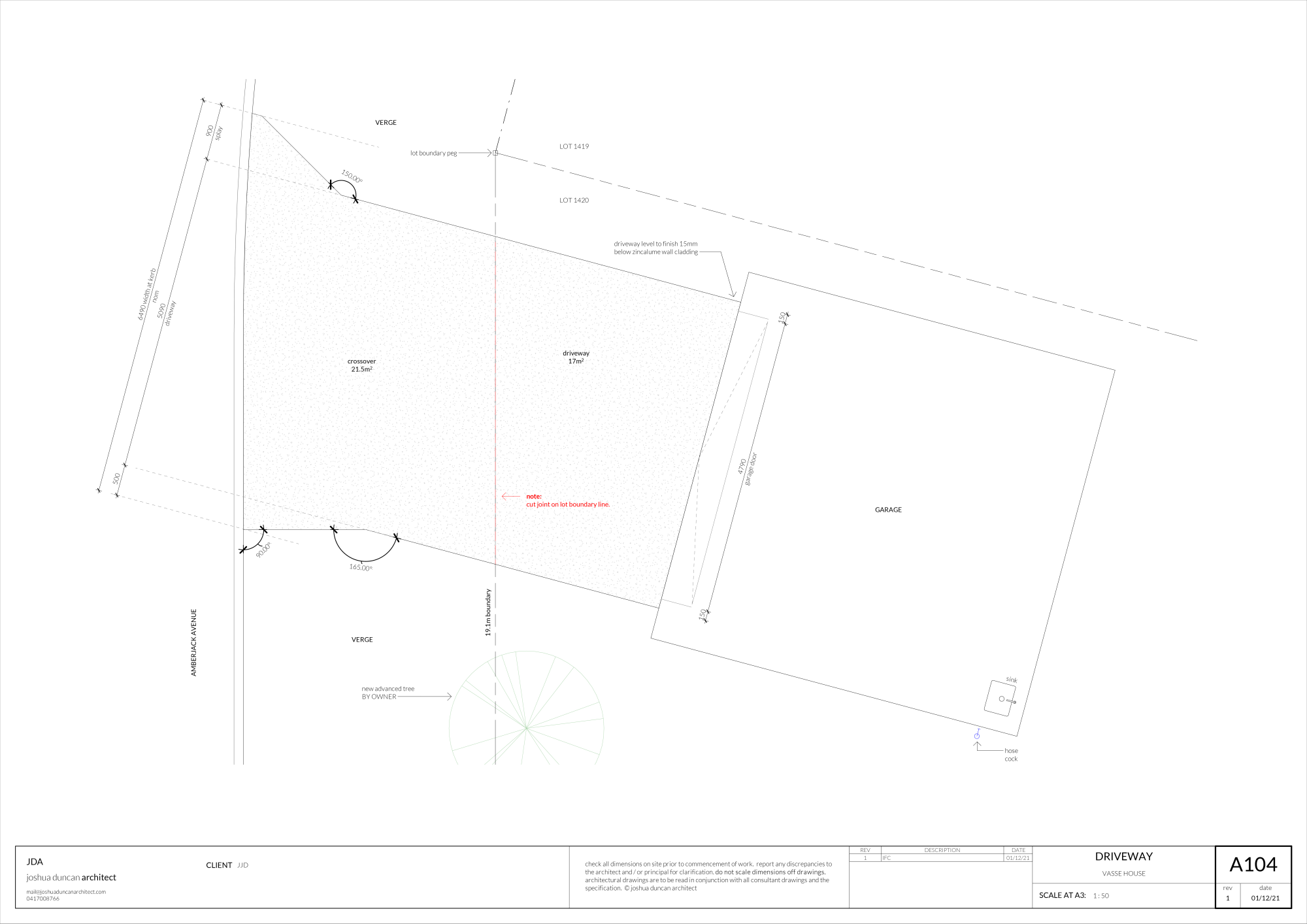

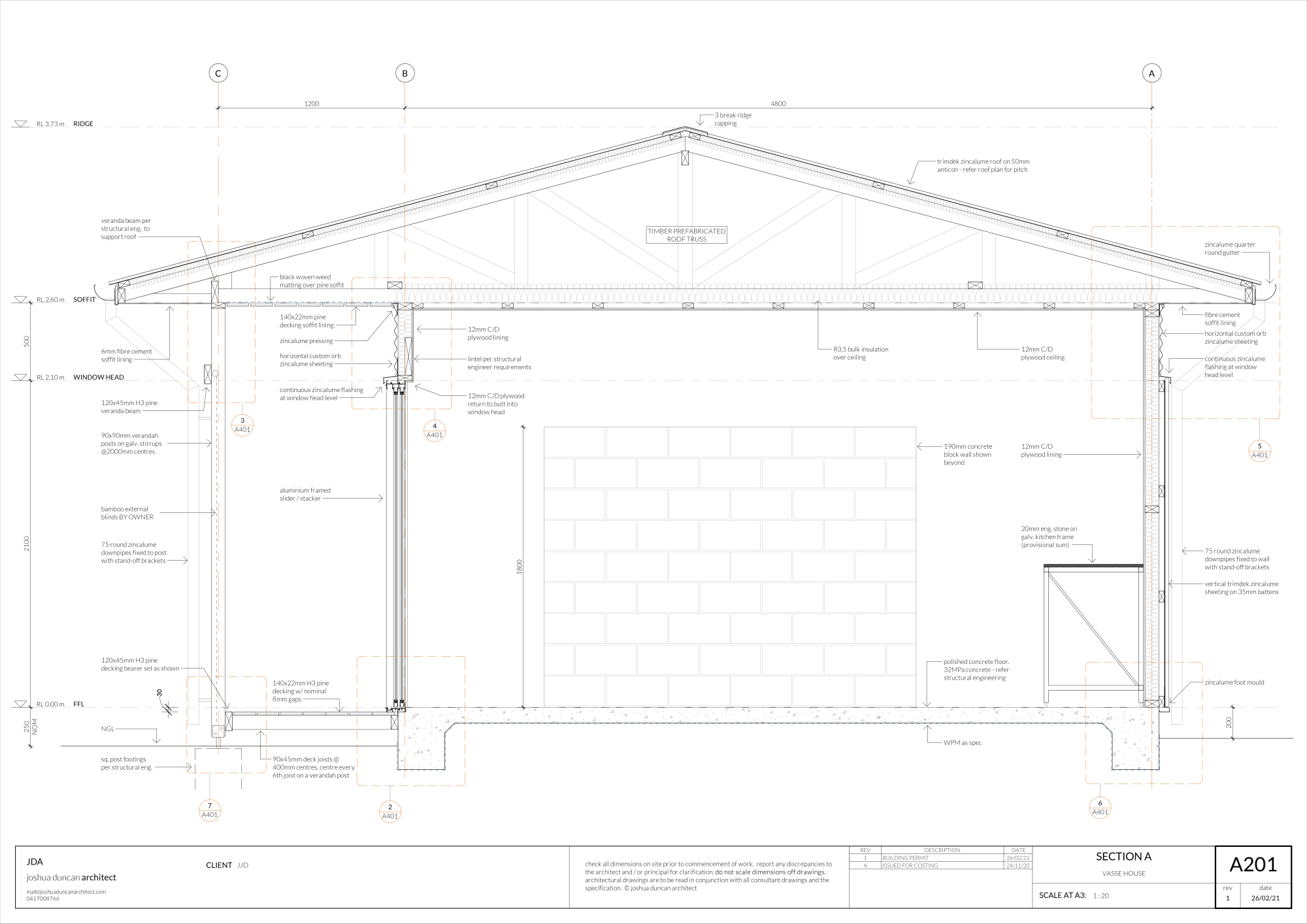

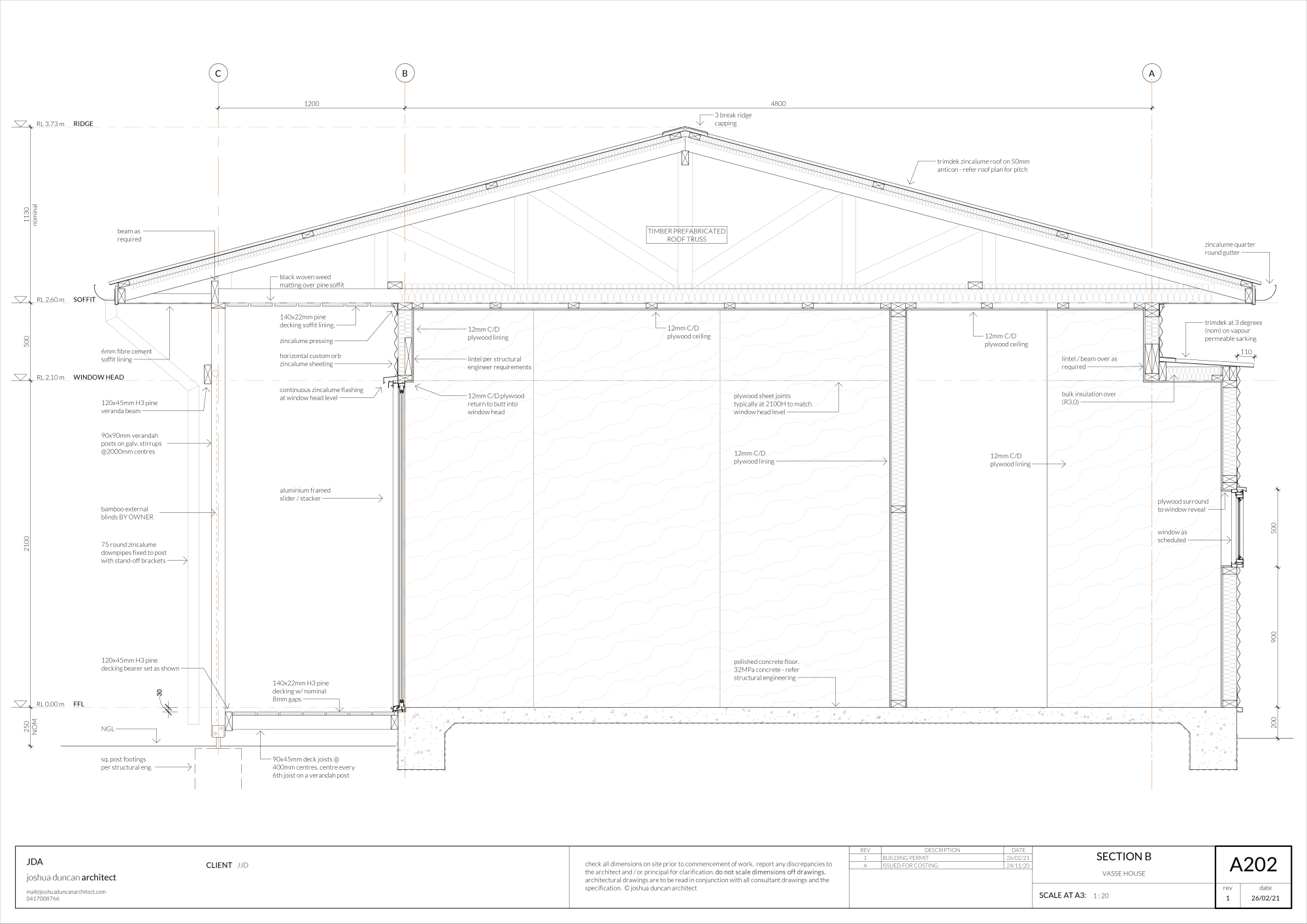

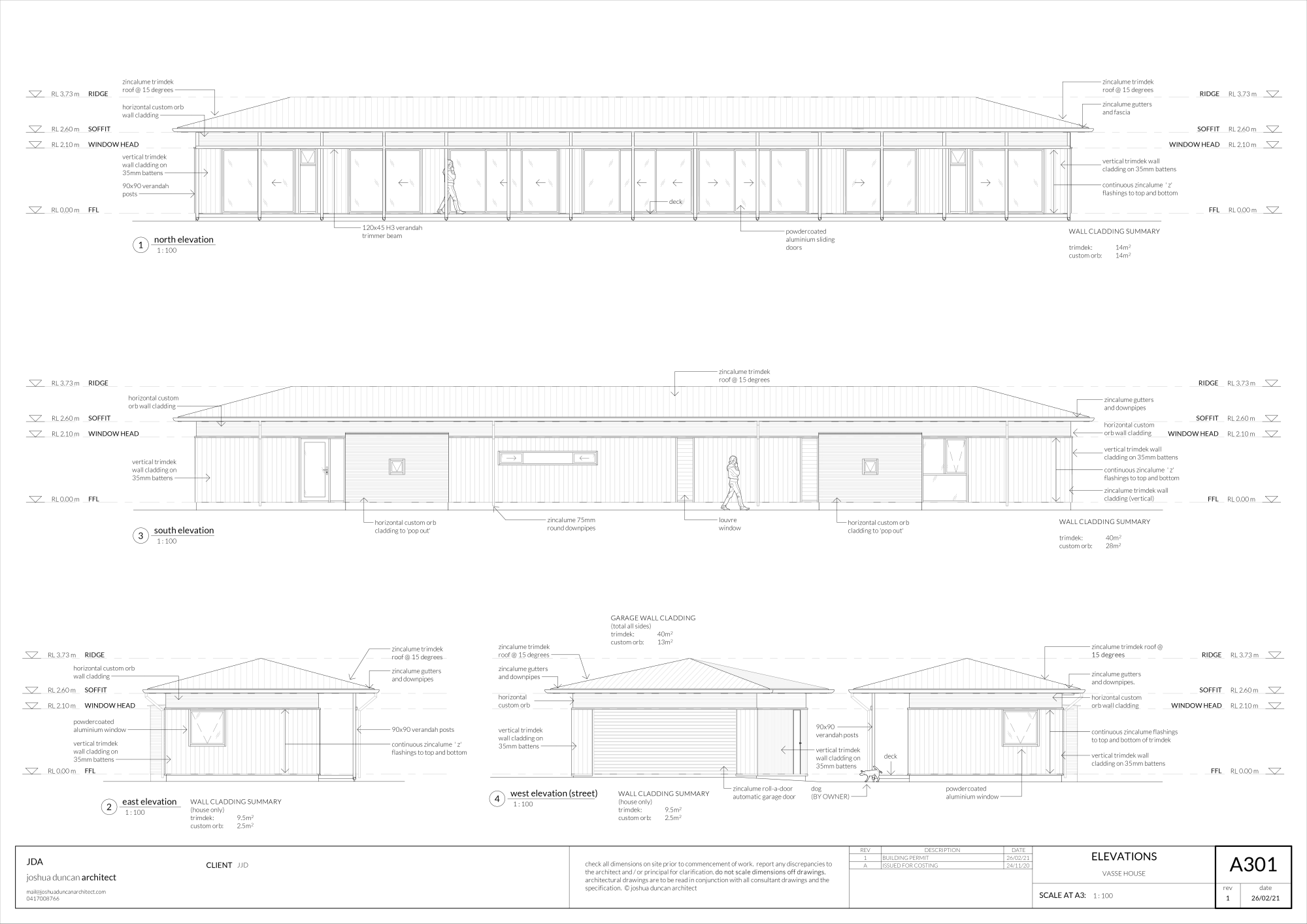

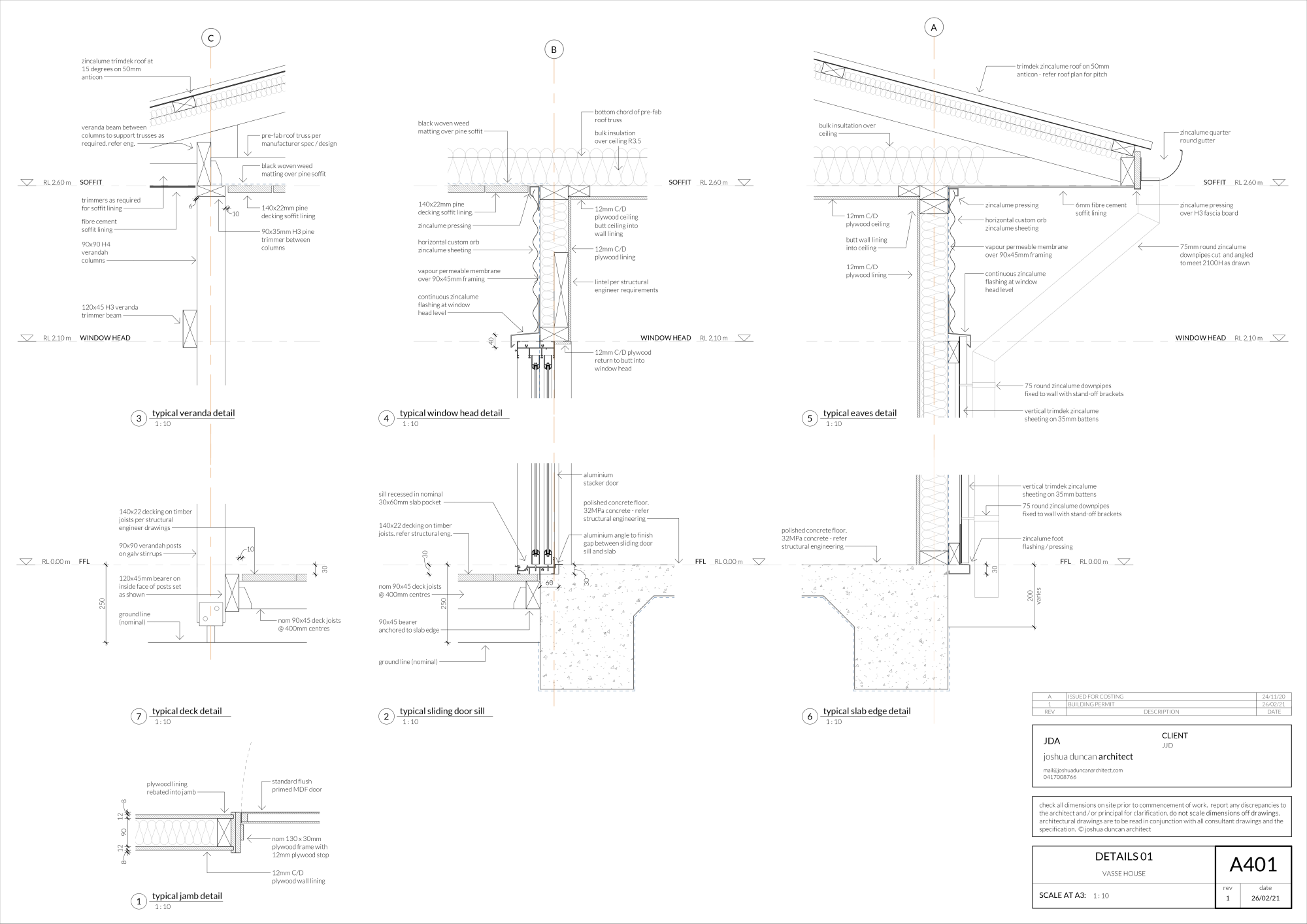

The house is an exercise in austerity. Pavilion One is a square carport, twisted in orientation to align with the north boundary. Pavilion Two, the house proper, is oriented due north. 4.8m by 28m overall, 14 bays on a 2m grid sets out a simple plan. Four small rooms, two bathrooms, and two nooks symmetrically flank one big room. It is mostly closed to the south and mostly open to the north, facing the garden across a long, skinny verandah.

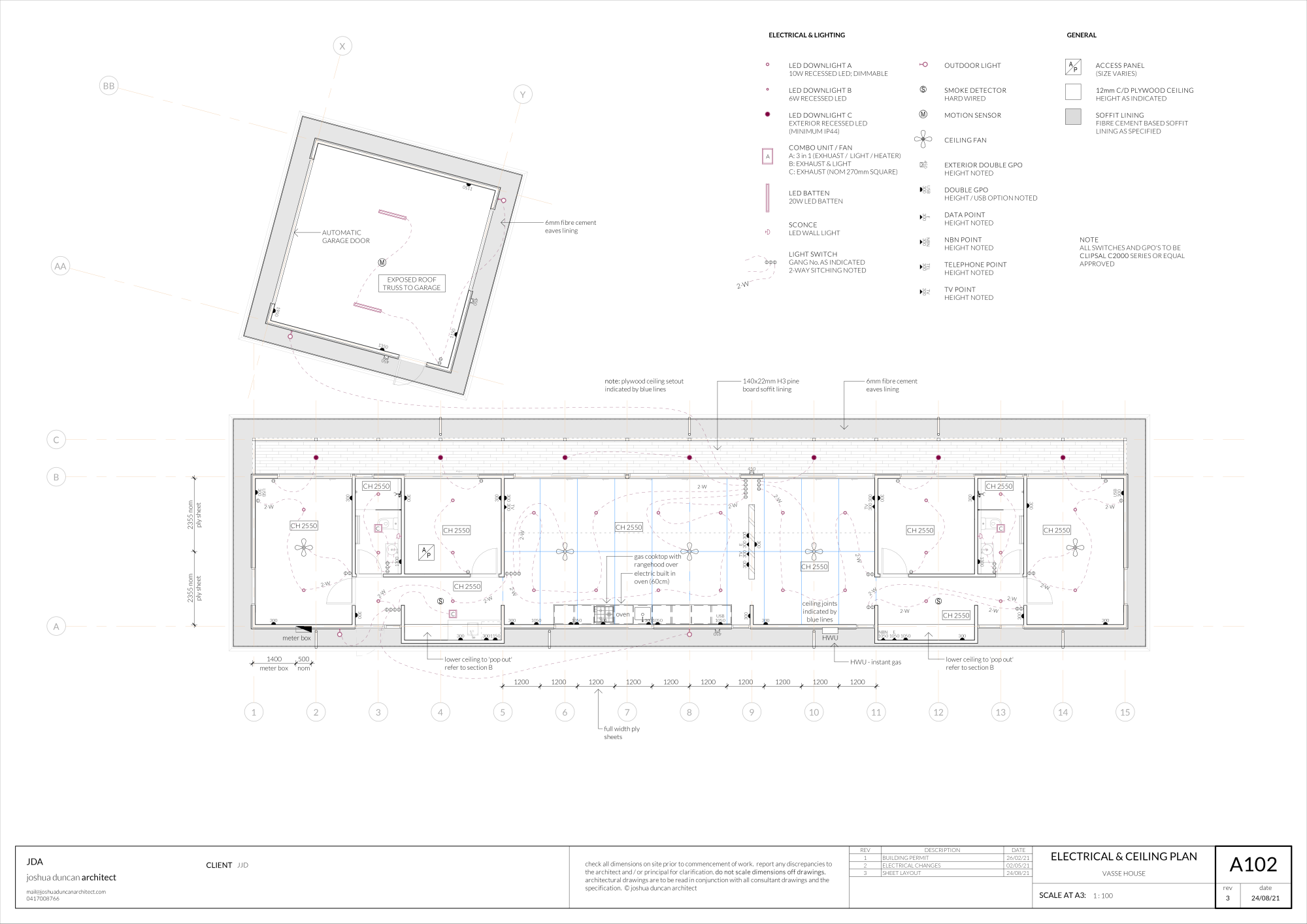

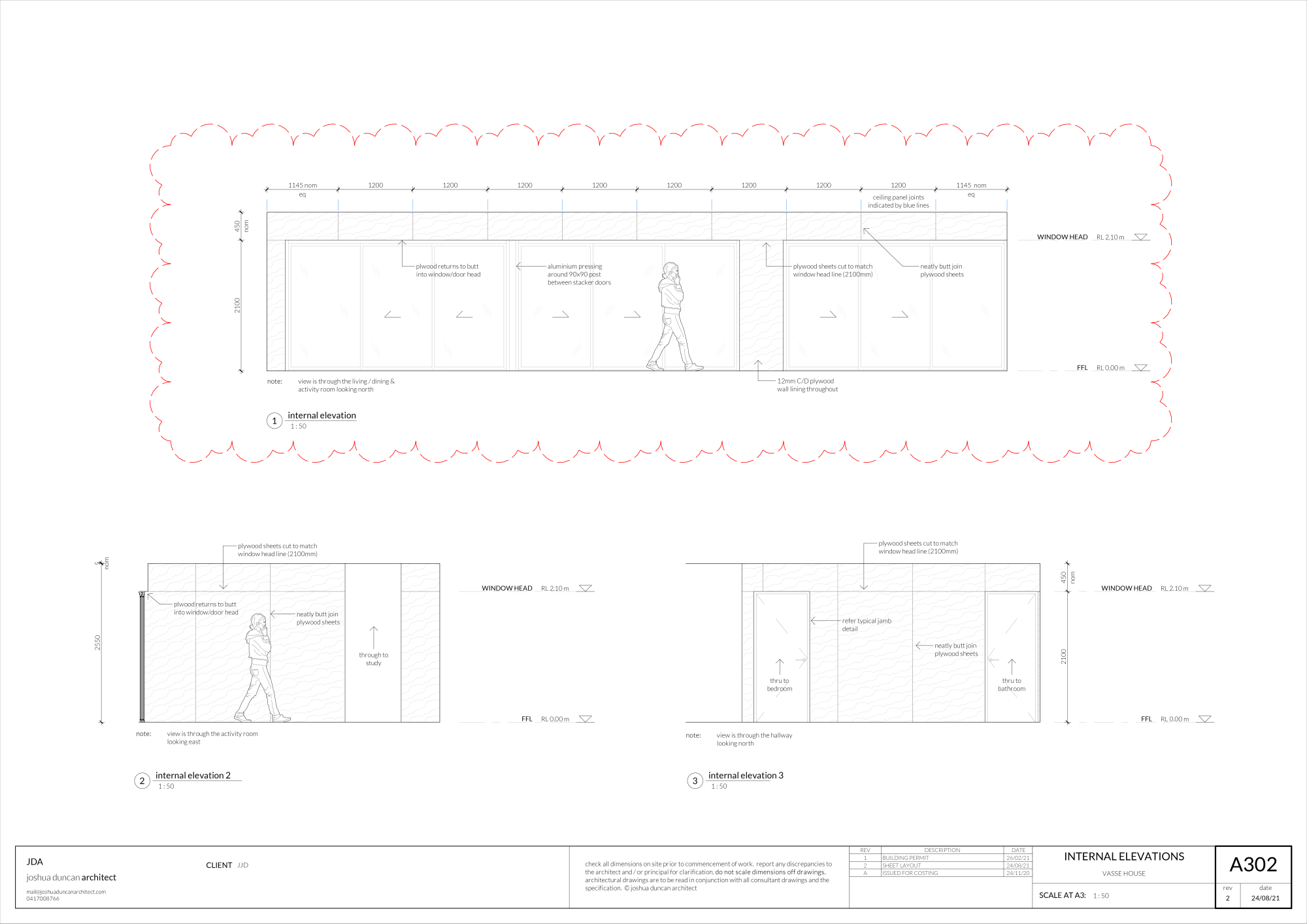

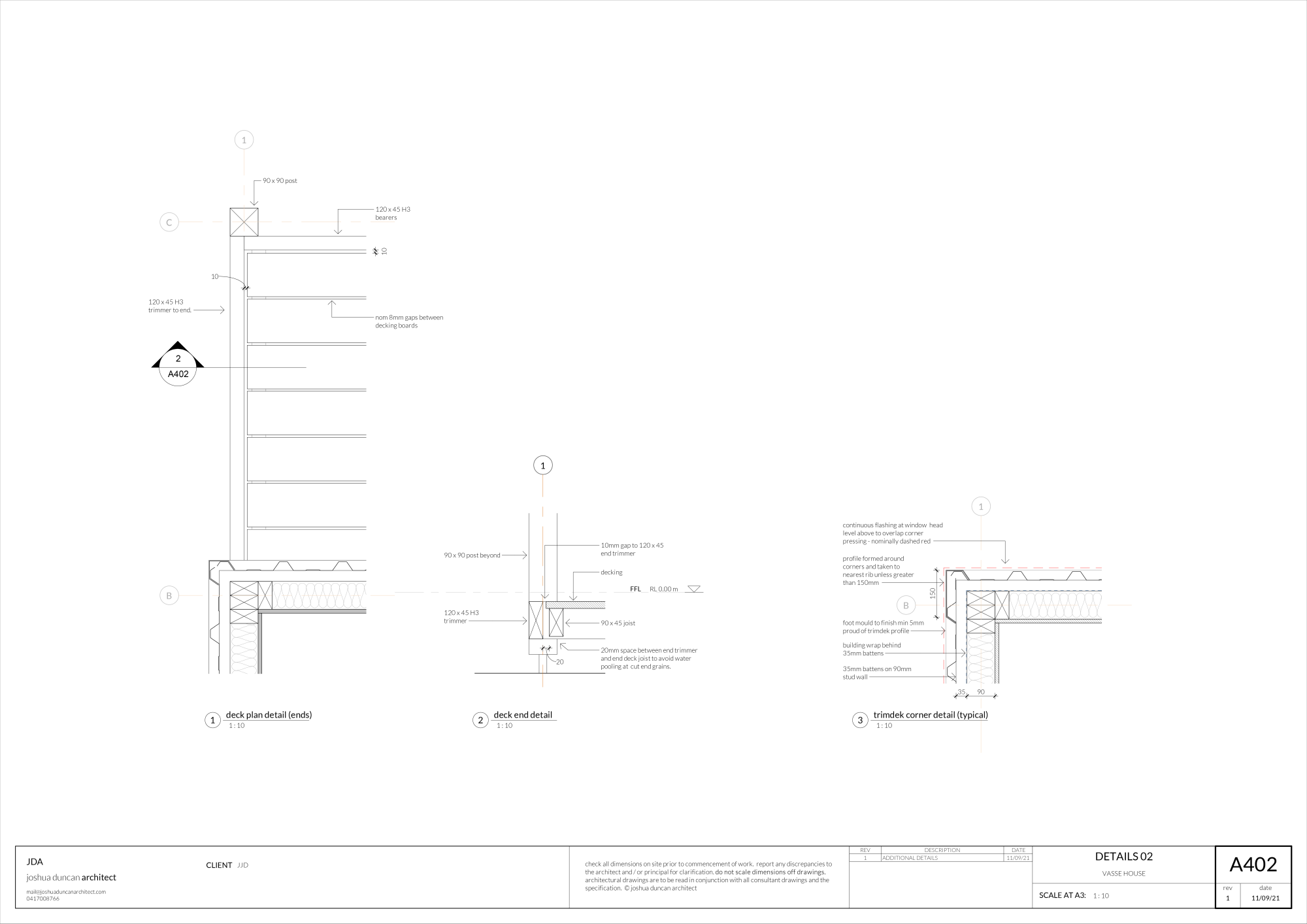

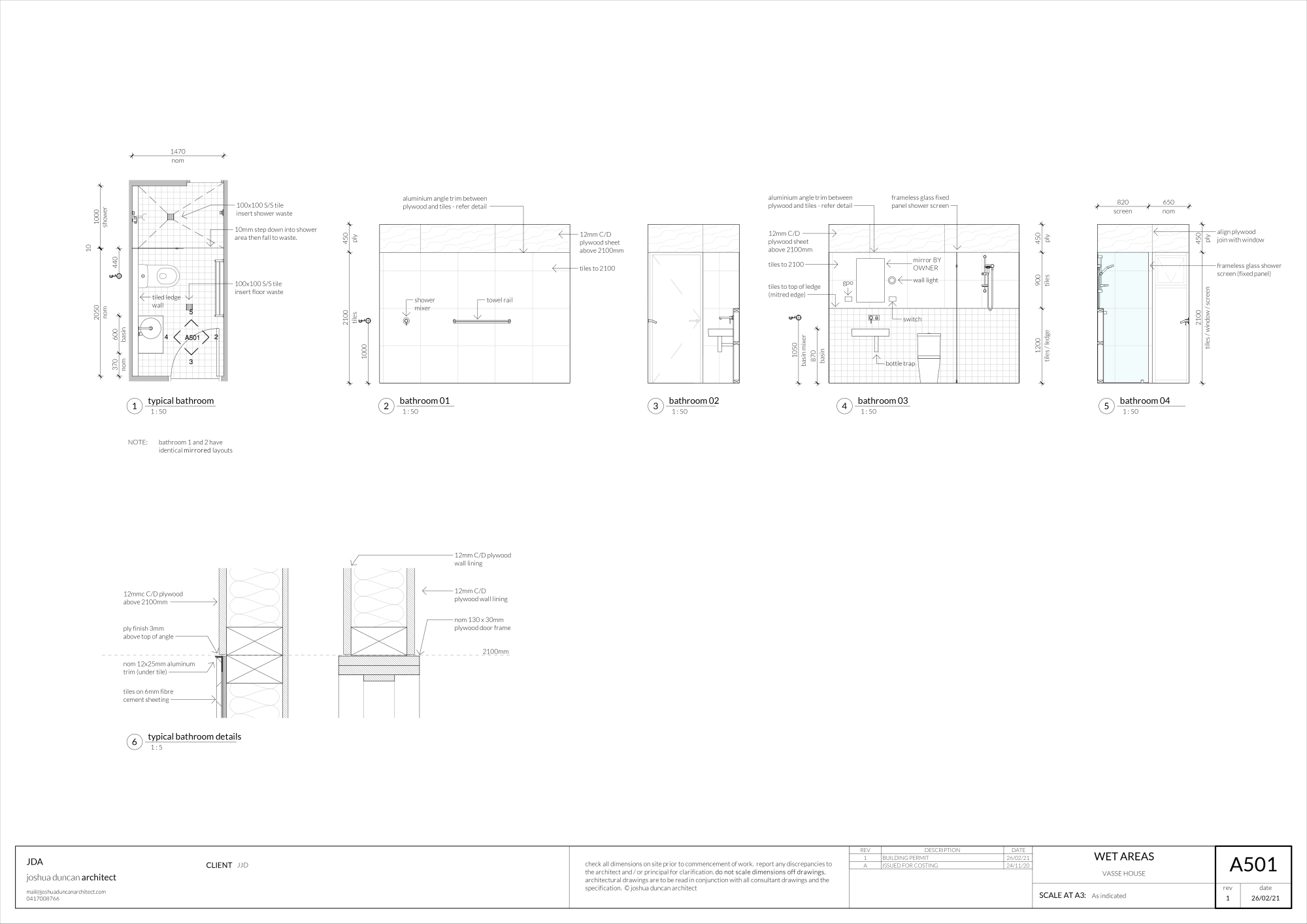

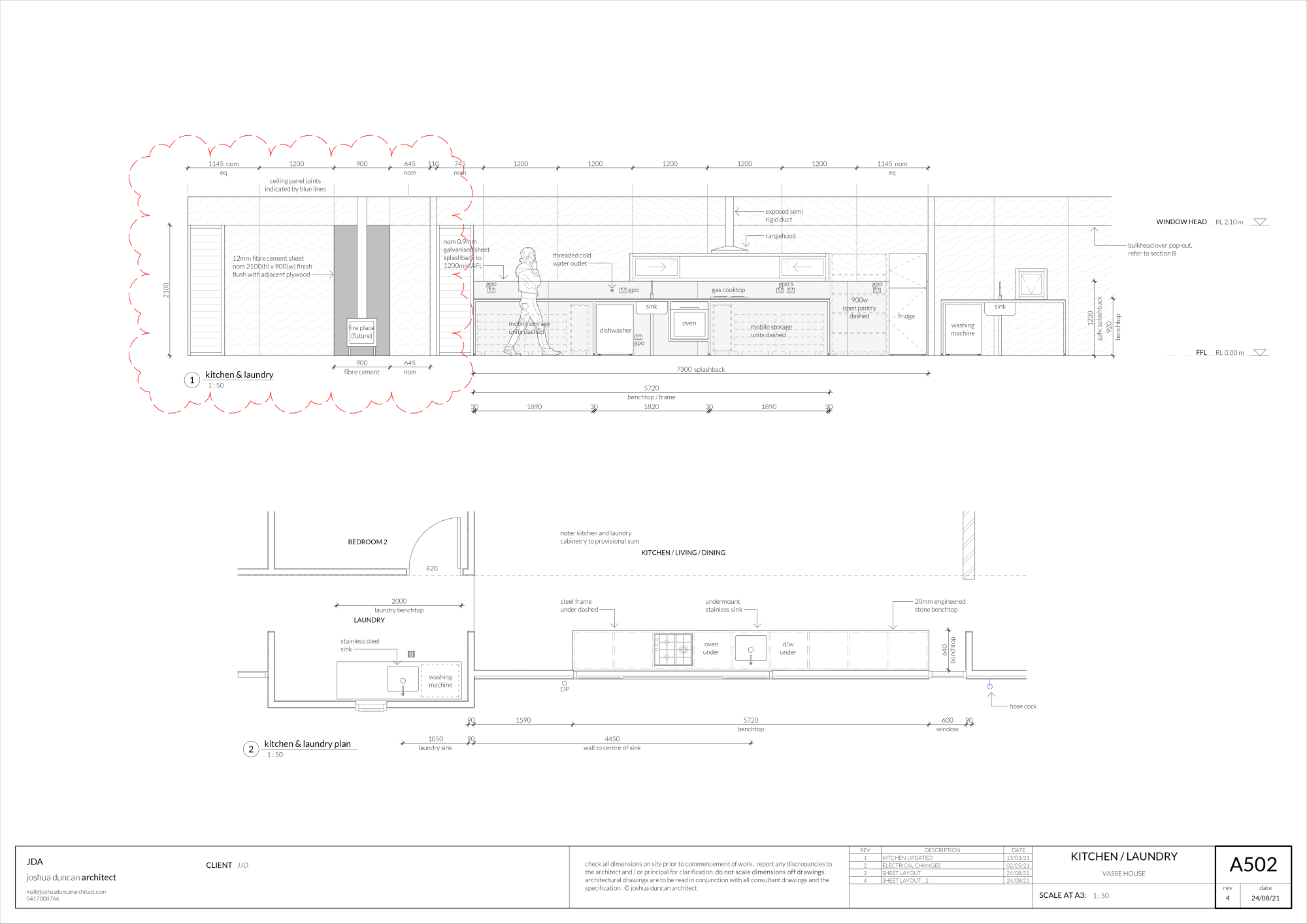

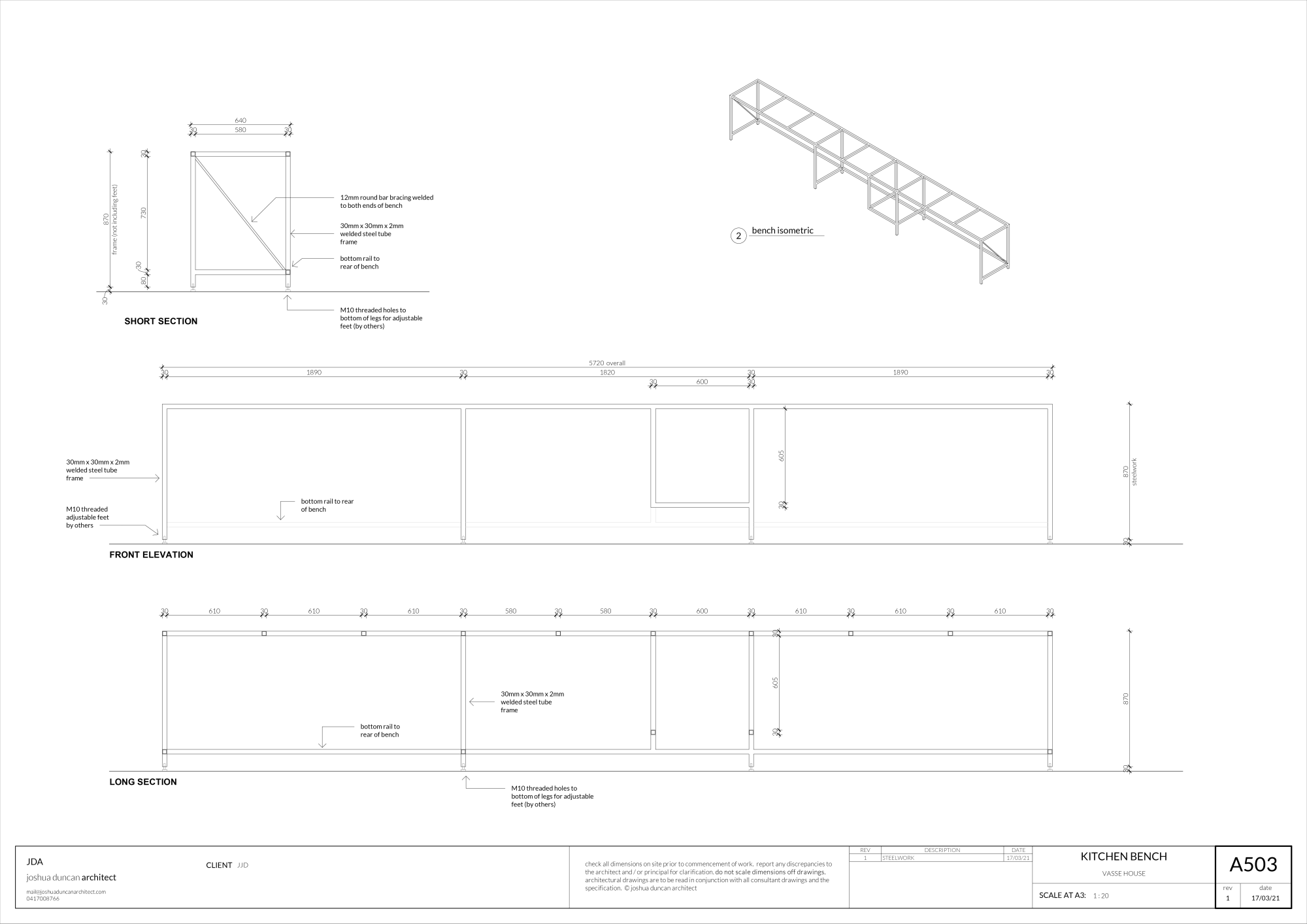

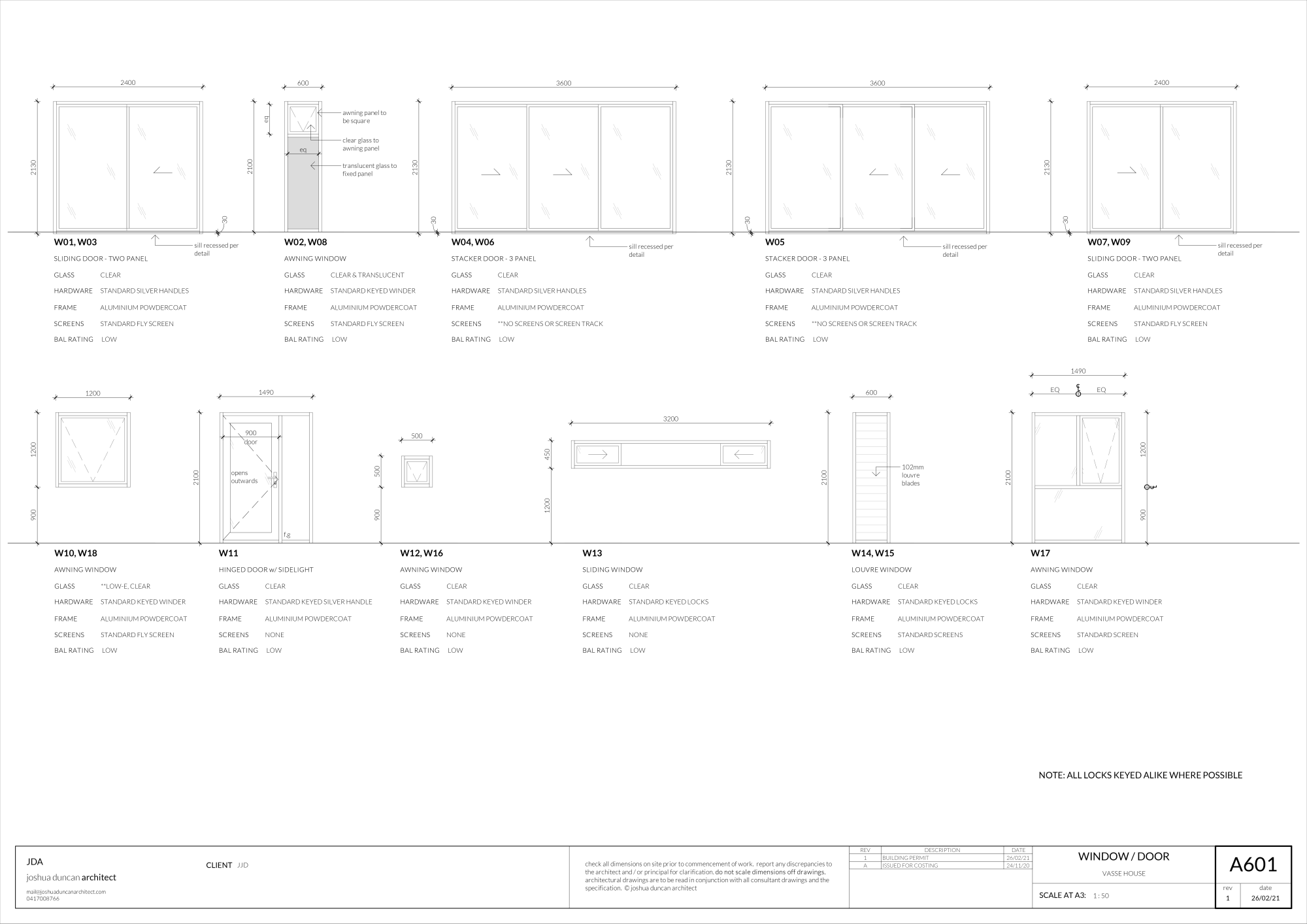

The efficiency in plan begets efficiency in construction. One prefabricated roof truss is repeated for the length of the house. 90mm stud walls are lined with plywood internally and Zincalume cladding externally, sitting atop a polished concrete slab.2 Two types of sliding aluminium door—two panels at 2400mm and three panels at 3600mm, the largest in the residential range before entering the pricier commercial suite—form the threshold to the garden, while the remaining facades are punctuated with minimal openings as required. The rigour is such that every now and then, room is left for moments of indulgence, if we can call them that—a second type of cladding (Custom Orb, as opposed to Trimdek) forms an entablature to the facade; a custom bench of 30mm SHSs holds the kitchen appliances; 12mm C/D grade plywood is neatly aligned to the window head and carefully butt-jointed together. It’s a balance that reflects what is included and omitted in its construction documents—16 pages of deliberately sparse drawings are all that are needed to build this house. One wonders if it could have been done off a plan and section alone.

With a budget of $240,000, the house is comparable in cost to its neighbours. Like them, it offers four bedrooms, a two car garage, and a second living room. It’s built with the same stud walls, sits on the same slab-on-ground, and is topped with the very same tin roof of its compatriots. But the difference is clear. Neighbouring dwellings are entered through a solid front door, or, more commonly, through the internal door connecting carport to hall. This move—a staple of the new suburban home—effectively shuts the house off to the street, allowing one to go from home to work and back again without ever leaving the climatically sealed zones of private space. Vasse House, on the other hand, separates the carport from the dwelling itself and allows a direct line of sight from street to garden.3 Where other houses in the area fill the width of their site, Vasse House occupies only half of the lot. Where others succumb to a warren of corridors—pushing the living and al fresco dining to the rear of the site and leaving the (all too often astroturfed) garden to cover what land there is left—Vasse House aligns to the north and opens to it, giving each room egalitarian access to light, a verandah, and a view of the rambling garden. The tools of the project home are all here, but the result is worlds apart. Perhaps this exercise in austerity is actually an exercise in generosity.

The documents below—ruthlessly terse and cheekily direct—outline a possibility for living in the suburbs. The housing crisis is a beast of a problem, and one that calls for structural and holistic responses. A well designed house won’t solve it, but maybe a good set of drawings, a suburban plot of land, and two garden sheds is a start.

-

‘Kealy House’ was already taken by the house completed by Joshua for his brother in the same year. ↩︎

-

Zincalume is a coating product applied to steel, commonly used for roofing. ↩︎

-

In keeping with the ethos of the house, the plants that make up the garden are of course sourced mainly from Bunnings. ↩︎

Joshua Duncan is an architect practising in WA across the Perth and Southwest regions. Josh is interested in creating extra-ordinary buildings with ordinary formal, material, and economic means.