Tracing History

Rowan Lear

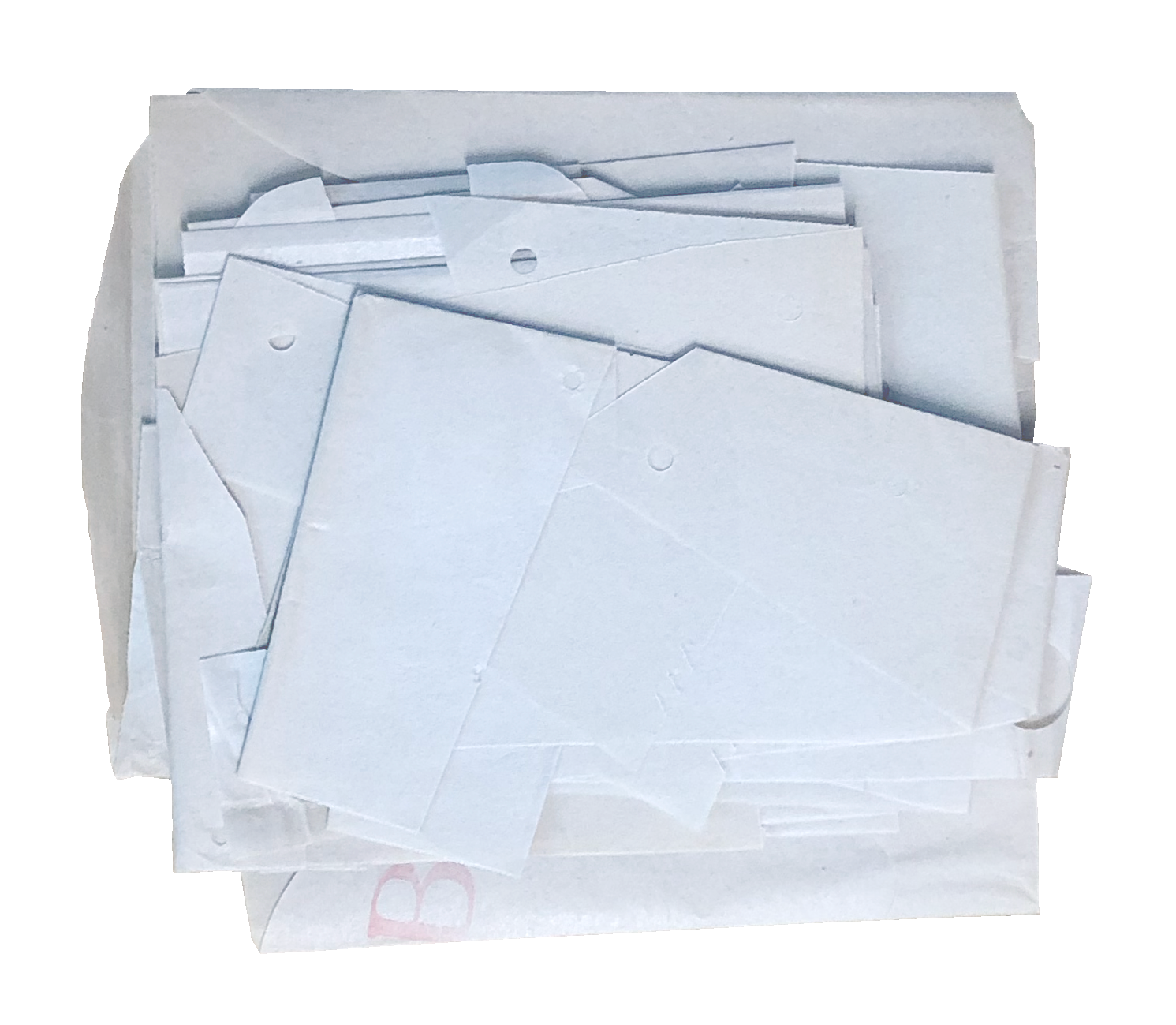

In an unassuming cabinet at Sydney’s Caroline Simpson Archive, stuffed between yellowing trade catalogues, is a card envelope approximately 15 by 25 centimetres in size. Within are seven folded, irregular pieces of waxed paper and an A5 booklet of instructions. On the front of the envelope is the title Pattern No.2 “DIVAN”, with a drawing of a simple, elegant, mid-century daybed. Nine years before IKEA’s seminal Lovet table and a generation before Enzo Mari’s Autoproteggazione, Fred Ward leveraged soft education, aspirations of autonomy and Australia Post to bring high quality furnishing into the homes of working class Australians.

Fred Ward emerged as one of Australia’s premier designers from the 1930s through till the ‘60s with a strong streak for democratising access to high-quality design, though his work has since fallen from popularity. Ward was born in Melbourne in 1900, and raised in suburban Black Rock, Victoria. Initially working in art, illustration and cartoons, he came to professional furniture design after a stint designing the furniture for his Heidelberg home1 as a member of the neighbourhood’s prominent avant-garde scene.2 During the Depression, his penchant for cost-accessible design became apparent with his 1932 Unit Range for Myer: he proposed these pieces as a more affordable alternative to the then dominant model of purchasing whole matching suites of furniture. The pieces were designed to match, but did away with the expectation of completeness. Pieces could be omitted from the set or purchased later, depending on the space, finances or needs of the household.3 The series drew from contemporary European modernist sensibilities: all angular, basic geometries, pairing exposed timber frames with simple upholstered cushions. This, in turn, allowed the textiles to be updated with only household skills, in pace with changing trends, rather than requiring them to be professionally reupholstered or replaced entirely.4

When Australia entered the second world war in 1939, the Royal Australian Air Force employed Ward to coordinate the manufacture of British-designed warplanes locally.5 These aircraft were being made by a workforce who, for the most part, had never had to make aeroplanes before. Ward’s challenge was to simplify the manufacture of these planes and figure out ways of instructing the low-skilled workforce on their construction. Among other methods, he developed a “shadow board” of the aircrafts’ components: silhouettes of the parts which the workers could refer to as they honed the unfamiliar pieces. In the wake of the war, Australia’s slow retooling from its wartime economy, combined with the influx of returning servicemen, led to material, labour and housing shortages across the country. Ward, recognising that high quality furniture was out of reach for the swathes of new, young Australian homeowners, decided to take the techniques he had developed for aircraft and apply them to furniture. In 1947, two years after the end of the war, Fred Ward launched his Patterncraft series.

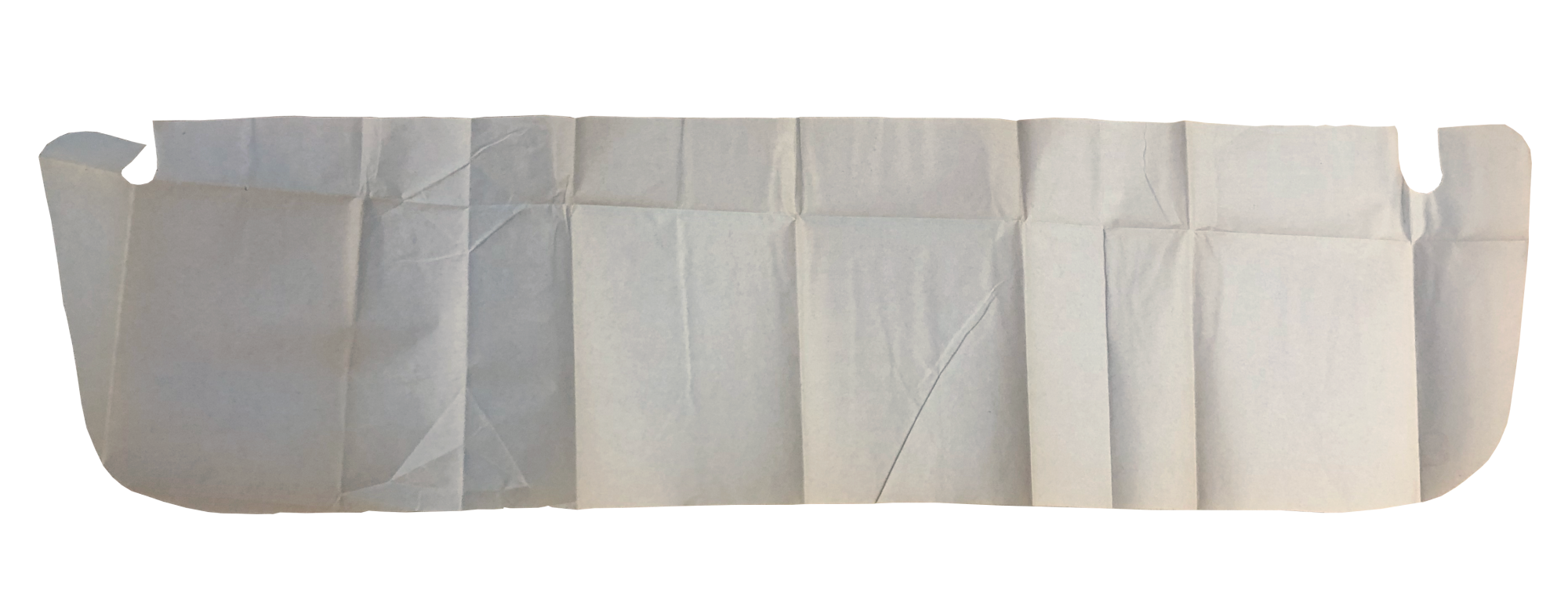

The “pattern” of its title is from the same sense of a sewing pattern: paper stencils used to transfer the cut-lines of fabrics prior to sewing. Rather than selling the furniture pieces, Ward sold the designs’ patterns by mail-order: simple enough for the broader, relatively unskilled Australian population to cut, build and finish. As it says on the patterns’ envelope: “no special skill or tools are needed to make this modern furniture.” The Patterncraft series was designed in the style of American Arts & Crafts, defined by gently curving corners and an aversion to parallel edges, balanced with a degree of sobriety and heft, instead of the more rigidly European modernist sensibilities of Ward’s earlier work. This was a gesture to appeal more broadly to popular tastes, rather than a sophisticated avant-garde consumer, as part of Ward’s societal aspirations for the designs.6 These were pieces intended for “everyday Australians,” rather than a wealthier clientele of more progressive taste. This concession to popularity rather than aspiring to timeless “high design” may have contributed to the line’s declining popularity in following years. Even now, the pieces have an air of being deeply attached to their era. The ability to trace the patterns’ profiles onto the pieces of timber allowed Ward to depart from over-reliance on straight lines and right angles. The chairs he designed outside of the Patterncraft line almost exclusively eschewed perfect verticals and horizontals, and the pattern allowed him to pass this technique onto a less experienced craftsperson.7 The line’s flagship piece, the “Occasional Chair,” prominently demonstrates this. The signature combined frame-and-leg piece angles gently from its front, down to the ground at the rear, before curving back up to meet the seat cushion. It would be near impossible to measure this out onto a piece of timber accurately and then confidently cut without access to professional equipment, however, the pattern-transfer technique eliminated this barrier. During their heyday, these pieces were massively popular, befitting their low-cost and elegant broad appeal.

In 1950 Ward left the project to work on grander commissions in Canberra. Patterncraft was succeeded by Plycraft, a line designed by Walter Gherardin and Ron Rosenfeldt.8 As the name suggests, Plycraft replaced Patterncraft’s solid timber with plywood, which was by that point cheap and already popular, in part thanks to the Eames’ earlier innovations. Whether due to the flat material qualities of ply, with its strongly contrasting plain face and banded edge, or Gherardin and Rosenfeldt’s stiffer design sensibilities, Plycraft lacked the unassuming grace of Ward’s work. By the mid ‘50s, the Australian consumer economy was once again on the rise, beginning to suggest the conspicuous middle class wealth for which Australia is now known. As a result of the greater access to affordable consumer goods, the demand for the cheap but effort-intensive Patterncraft and Plycraft series dwindled. Interestingly, during this time Ward had promoted a parallel venture called Timber-Pack. Timber-Pack took the designs of Patterncraft but pre-machined the components so that all consumers had to do upon delivery was assemble the pieces. This eerily prefigures Gillis Lundgren and Ingvar Kamprad’s “invention” of flat-pack furniture under the moniker IKEA by nine years.7

In the years since, the consolidation (or intensification) of furniture mass-production and the drift of jobs from workbench to desk has mystified the origins of our possessions. In 1966, the first recorded year of the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 26% of employed Australians worked in manufacturing. A further 18% worked as tradespeople and labourers and 12% in the hands-on industries of farming, fishing and timber-getting.9 With the outsourcing of manufacturing and other blue-collar work over the past six decades, Australians now work overwhelmingly in the service sector: in recent years manufacturing comprised only 7.7% of Australian jobs, while technicians and tradespeople make up 14%. Professionals and clerical & administration workers dominate the workforce at 22% and 15%, respectively.10 This has pushed fluency in tactile skills to the fringes of our economy.

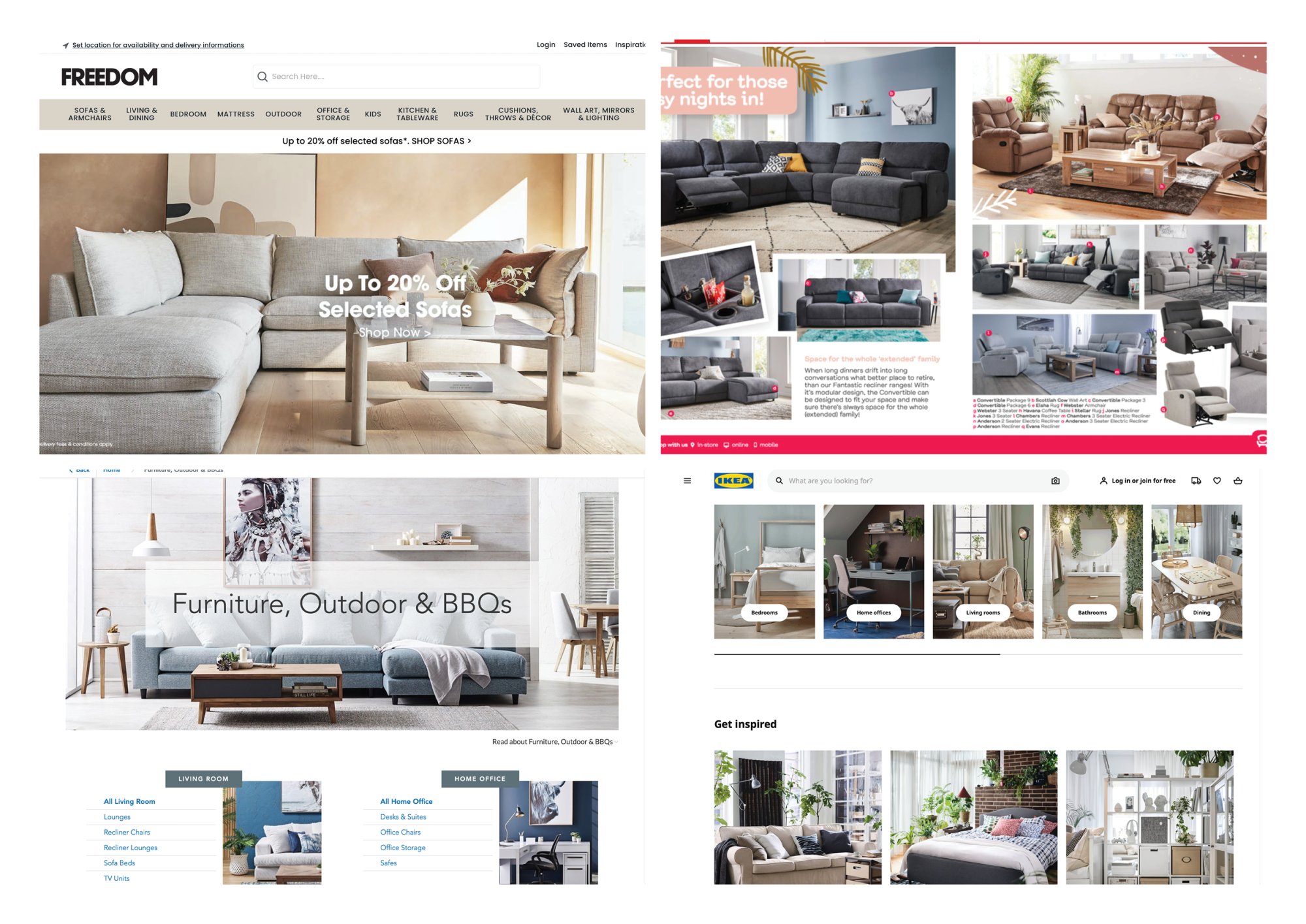

Alongside these demographic changes, low-costs and the accelerating pace of trends have made furniture disposable: before the Second World War furniture sets were considered multi-generational assets, which seems unthinkable today.11 This throwaway mindset fits poorly with contemporary aspirations of sustainability. We discard rather than alter furniture which no longer sufficiently meets our needs. Though we may suspect that this is bad, we are typically left with few alternatives. Recent aesthetic trends in domestic furniture intend to mask how things are made, though this is likely a result of cheap manufacturing practices rather than any real consumer preference. The product catalogues of Harvey Norman, Freedom, Fantastic Furniture and IKEA—Australia’s big four in furniture 12—are awash with chunky, fully upholstered lounge-chairs and trendy veneers glued onto MDF, often concealing honeycomb paper filling. These composite assemblages are troublesome for a few reasons. Recycling these composite pieces is more difficult than standard recycling, meaning that 85% of furniture left on the kerb is not recycled.13 The dominance of engineered wood clad in veneer makes for short-lived finishes that cannot be sanded back or retreated to lengthen their lifespan and the concealed frame (either by fabric or veneer) makes altering pieces challenging.14 The rapid turnover of trends exacerbates this convenience to replace rather than repair or renew.

On face value, Patterncraft’s agenda was about access: granting working class Australians access to better furniture at a lower cost. However, like any DIY initiative worth its salt, the underlying agenda was education. As the customer saws, drills, notches, sands, and screws together their new chair or shelf from what had previously been a few planks of wood, they learn to understand how the other pieces in their life have been cut, drilled and so forth, and how those same pieces might be sawn, screwed and sanded on their terms. This is what brings Ward’s Patterncraft model into contemporary relevance. It is plain that our current set of circumstances are a far cry from post-war austerity: our problem is one of abundance, though an abundance besmirched by poor labour practices and flagrant disregard for sustainable material lifecycles. This prompts the case for a pattern-based mode of design. If sustainable and ethical furnishings are absent from shops, or priced out of reach, then DIY can fill that gap, and design patterns in turn can substitute the missing tactile knowledge.

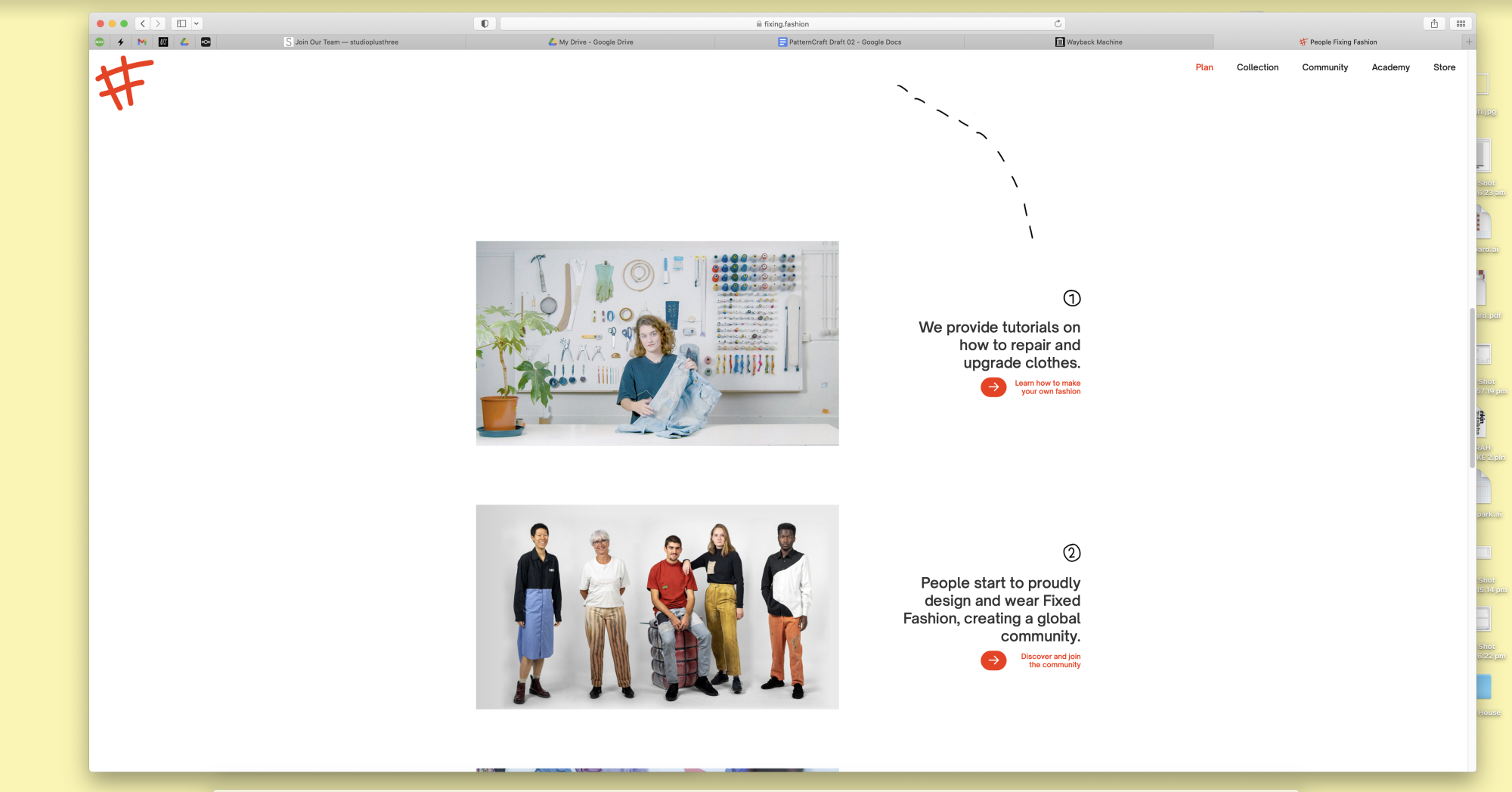

Fashion, along with most forms of consumer goods’ production, has endured a similar recent history to furniture-making: that is the adoption of low-quality materials and assembly to allow ever-lowering costs and faster replacement. The practices of mending and altering one’s own clothes is still familiar, though much less frequent since the advent of fast-fashion. However, the recent Slow Fashion movement has brought on a revival of these attitudes. The Dutch start-up Fixing.Fashion replaces mail-order paper patterns with a web-based platform: social-media style inspiration, an archive of techniques, and a short-video academy all tooled to establish a repair-oriented aesthetics: actively embracing the stitch, the darn, the patch, the dye and the mismatch.15 A pattern-based culture of furniture design could similarly extend into the everyday. The potential for web-based, printable patterns is logical. However it could reach further, employing the same techniques to promote an understanding of how to repair or alter our furnishings to keep pace with our needs: how you could turn a three-seater couch into a two-seater and an armchair if you move into a smaller flat, or how a bookshelf might be extended in step with an enthusiastic book-buying habit. To establish an aesthetic which embraces the alteration rather than conceals it. To learn to identify which pieces of furniture will lend itself to felicitous alteration (solid timber, exposed frame, separate cushioning) and thus a longer life, opposed to those which preclude it (full-upholstery, MDF, veneer).

Our possessions inhabit a strange role in our homes.16 To liken them to pets would be sentimental to the point of hoarding. But, to consider them only as what gets between ourselves and the floor seems brutishly materialist. Our possessions may be material, but at their best, it’s material with attitude. However, their inanimacy alienates them from us; they sit in a space between lively and lifeless, which doesn’t come with a clear code of behaviour. Preparing and assembling the components of furniture may help us understand our possessions better: not only in material terms as outlined in the previous paragraph, but also how we relate to them. As the boards of timber and rolls of upholstery fabric become useful, how too they attain personality.

-

Nanette Carter, ‘Ward, Frederick Charles (Fred) (1900–1990)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2012, accessed online 2 November 2022. ↩︎

-

Heidelberg had begun attracting artists in the late 19th century, when it was part of Melbourne’s rural fringe. The artists there, among them Arthur Streeton and Frederick McCubbin, founded the Heidelberg School, the first distinctly European-Australian art movement. The neighbourhood continued to attract Victoria’s progressive creatives, including architects the Burley-Griffins and later Robin Boyd as well as the Heide contingent, down the road at Templestowe, with whom Ward became personally affiliated. ↩︎

-

Jason Harris, Fred Ward: Visionary Modernist Designer, Scammells Auctions, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

Nanette Carter, Blueprint to Patterncraft: DIY Furniture Patterns and Packs in Post-War Australia, University of Swinburne, Melbourne, accessed online 2 November 2022, now only available through the Internet Archive. ↩︎

-

F.D. Wrigley, Fred Ward: Australian pioneer designer 1900-1990, 2013 published by the author in Canberra, Australia, p215. ↩︎

-

This is in strong contrast to the more widely cited champion of home-built furniture, Enzo Mari. Mari’s 1974 Autoprogettazione combined extremely basic furniture construction techniques with angular avant-garde aesthetics to bring cutting edge design into the homes of the masses. ↩︎

-

Furniture Pack Solutions, The History of Flatpack Furniture, Furniture Pack Solutions, Swansea UK, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Sydney Living Museums, Furniture from Paper Patterns, Sydney Living Museums, Sydney NSW, accessed online 2 November 2022. ↩︎

-

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Fifty Years of Labour Force: Now and Then, Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Canberra ACT, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

Labour Market Insights, Industry Information: Manufacturing Australian Government, Canberra ACT, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

Molly Blackall, Will Ikea’s recycling scheme really make it greener?, The Guardian 2021, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

IbisWorld, Furniture Retailing in Australia - Market Research Report, IbisWorld 2022, accessed online 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

War On Waste, Series 2, Episode 2, 2018, segment starts at 32:32, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney, 31 July, viewed 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

Mark Vender, ‘Landfill: Australia’s ‘underground’ furniture movement’, Handkrafted blog, Australia, viewed 2 November 2022 ↩︎

-

fixing.fashion, which is their name, but also the URL of their website. No ‘.com’ or ‘.net’. If you type ‘fixing.fashion’ into your URL bar, it will take you directly to their website. ↩︎

-

For more along this line of thought, see Sam Jacob’s essay Life Amongst Things, written for MacGuffin Issue 5 The Cabinet (Winter 2017/Spring 2018) ↩︎

Rowan (he/him) is a designer and writer currently living and working on Gadi Country. His writing and design strive to engage with a meaningful aesthetics of repair and the responsibilities of designing for a long future. He has taught in the architecture schools at University of Technology, Sydney & Sydney University and his work has been exhibited at the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale and the 2022 Versaille Biennale of Architecture and Landscape Architecture.