The Limits Within the Lot

Kieran Patrick

“The more that Londoners are packed into a tiny space, the more repulsive and disgraceful becomes the brutal indifference with which they ignore their neighbours and selfishly concentrate upon their private affairs… Here indeed human society has been split into its component atoms.”

— Friedrich Engels, 18441

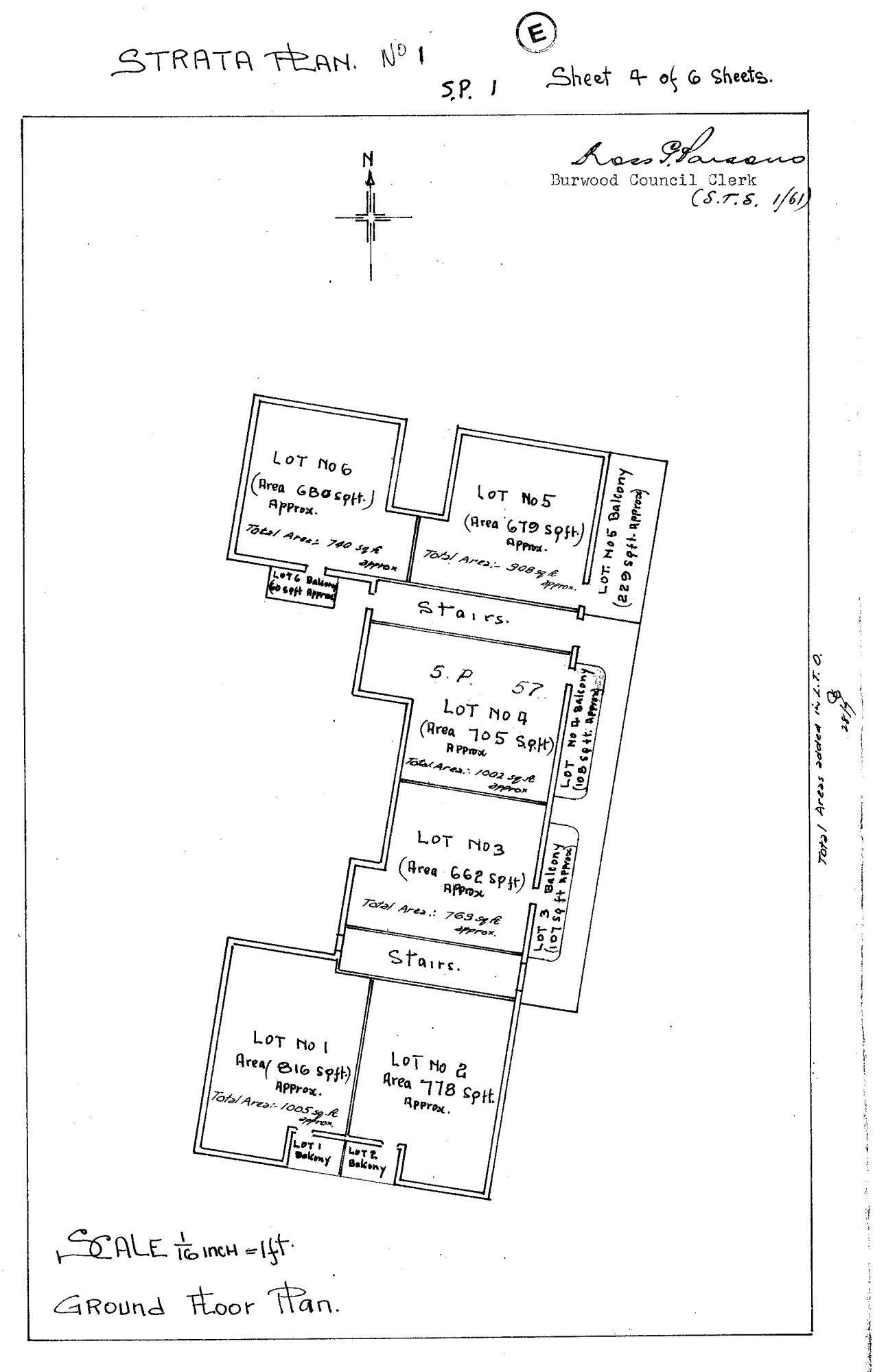

Around the time that the scaffolding is removed, the handrails are installed, and the landscaping is completed, all residential buildings of Class 2 status are measured and redrawn by a registered land surveyor.2 These drawings become what is known as the “strata plan,” a legal document containing a series of plans, sections, and tables which make clear the distinction of privately owned interior spaces within a commonly owned building.3

By virtue of this system of simultaneous common and private ownership, a legal entity known as the owners corporation is formed. This is a governing entity responsible for the management of a building along with the people who reside or work within it. Each owner automatically becomes a member of this entity and has associated legal and financial responsibilities to it.4

The origins of this form of ownership can be traced to the Puerto Rican condominio schemes established in the early 20th century.5 These condominios—from the Latin “con” and “dominium,” roughly translating to “joint ownership”—were the first to allow for multiple owners within a single building.6 This form of ownership later emerged in the United States as the modern apartment “condominium” in the late 1950s.7

In Australia, prior to the turn of the century, the first residential apartments emerged with the large manor houses built for the English landed gentry. As Sydney transformed from a colonial outpost into an industrial centre, a housing shortage saw these grand homes divided into smaller, leasable domestic spaces. The demand that led to the initial transformation of interior space eventually initiated the development of the city’s first purpose-built apartments in the early 1910s.8

The new building type emerging in the inner-city suburbs of Kings Cross and Potts Point took inspiration from the grand apartment buildings of New York and Chicago.9 These were owned through a single property title, and primarily built as rental housing.10 This trend continued into the 1930s with the development of larger and more complex apartment buildings facilitated by Company Title Ownership (CTO), a system in which an individual could hold a property title by purchasing shares of the private company managing a building.11

Alongside this period of urban densification was the extended transformation of surrounding farmland into modern residential suburbs. This process was spurred on by programs such as the 1928 Commonwealth State Housing Agreement12 and the development of the suburban tram and rail network, which formed the material basis of Australian suburbs.13 Post-war immigration and a continuing population boom saw mass relocation to these freshly minted suburbs, each new home with its own garden, clothesline, individual property title and mortgage.

As Australia’s population grew, a transformation of the suburbs was imminent. Prior to 1961, most new apartment buildings in Australia were developed by the state, along with several cooperative societies.14 Private developers, limited in scale of construction but eager to capitalise on the growing demand for apartment living, identified individualised ownership as a potential solution relating to capital costs. Meanwhile, a persistent housing shortage in the post-war era saw the establishment of the NSW Property Law Revision Committee in 1950, which was tasked with investigating the potential of apartment ownership.15

In 1957, to the irritation of the city’s development and construction industries, the committee deemed that CTO was a satisfactory means of owning and managing apartment buildings and recommended only minor changes. In response, a group of private industry leaders formed a consortium which lobbied for the introduction of the Stratified Titles Act.16 In 1958, this draft bill was put forward to the government of the day, and swiftly rejected. The consortium then proceeded to privately sponsor the development of an alternate bill.17 After being examined by the banking sector, the Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act of 1961 was bought into law. The following period—up to the recession of 1974—saw the construction and registration of over 10,000 strata-owned buildings in NSW.18

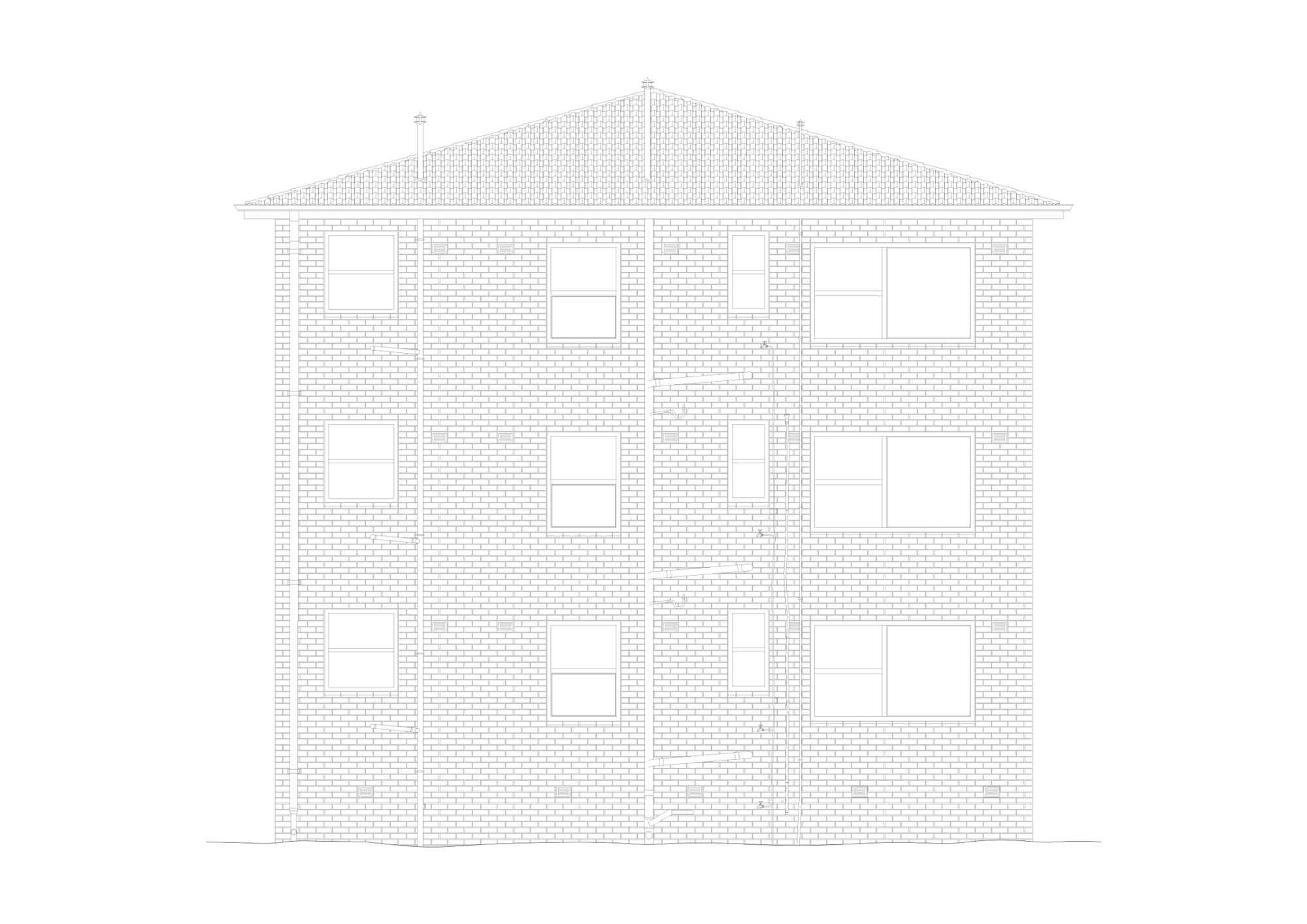

After this legislation passed, the red brick “walk-up” emerged as the most recognisable form of apartment building throughout Sydney. These buildings were generally built with double brick load-bearing walls on a reinforced concrete structure. They adhered to the same front setbacks of residential streets, but far exceeded the height and gross floor area of their neighbours. It is very uncommon to find a red brick apartment that does not feature a small patch of grass and a tree at the front. White timber window frames, door frames and fascias decorate the facades and are punctuated with cramped balconies and semi-ornate steel balustrades. These masses of earthy red are essentially scaled-up, bastardised versions of the red-brick bungalows that proliferated the suburbs of Sydney during the preceding decades.

Identical red-brick apartment buildings were often arrayed throughout entire streets. The ruthless efficiency of the plans and absence of rear gardens meant that up to six apartments could fit snugly into existing quarter-acre blocks. The building boom of the 1960s became the catalyst for the first design and planning controls that were gradually adopted throughout Sydney, along with the establishment of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act of 1979.19

The world’s first strata-owned residential apartment building is the neatly titled “Lindsay Gardens,” located at 189 Lindsay Street, Burwood. This three-storey building contains 18 two-bedroom apartments, which share a common laundry and four Hills Hoist washing lines. It is neighboured by buildings of a similar ilk and is entirely unremarkable in its setting. But in its ubiquity is its importance—it is a perfect example of the building type and scale that emerged as a result of the Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961.20

Seen purely as a form of housing supply, these buildings satisfied the ambitions of recent immigrants and aspiring homeowners, as well as provided “passive” income for the rentier class (48% of all strata-owned apartments are investor-owned).21 The supposed democratisation of apartment ownership, the image of these buildings and their domestic spaces, fulfilled a part of the Australian dream.

Through the Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961, each lot is defined in the strata plan. The word “lot” is used for all habitable spaces within a building. Each lot has a number which corresponds to the Certificate of Title, the specific unit noted on the strata plan, the number on the front door, and the schedule of unit entitlements within the ownership structure.

The ownership title of each individual lot relates to the floor area defined in the strata plan, and the volumetric space defined by the floor to ceiling height. In effect, when one purchases a lot in a strata plan, they are not purchasing the material of the building, but the airspace between the walls, floors, and ceilings. You can paint the walls but as soon as it dries, it becomes a part of the common property.22 The “Common Property” of a strata building is as any space or area within or outside of the building that is not included within a lot. These spaces are jointly owned by all owners.

The Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961 represents a unique form of ownership in that it affords private property rights within a commonly owned building. It is a form of freehold title property much like Torrens title property.23 The individual title holder has private ownership only within the airspace of their lot. The proverbial expression that “a man’s home is his castle” does not apply.

The formation of a strata title plan is made “real” by the completion of a building. Once an occupation certificate is granted and the registration of the strata plan is approved, the owner’s corporation is formed. This body is a legal entity and can be thought of as a fourth tier of urban governance.24 The corporation’s primary purpose is the management of the building and the people who own and or reside within it.

Along with the maintenance and operation of the building, the owner’s corporation and the respective committees are typically tasked with resolving issues relating to the parking of cars, noise complaints, the improper use of common spaces, and various odours that might permeate through a building.25 This governing body grants private citizens the ability to create laws (by-laws) that directly impact the lives of other private citizens.26 The use of BBQs, the drying of laundry on balconies, and the weight of domesticated animals are just some of the matters in which they have the deciding word.27

Though the owner’s corporation and associated committees are democratic in principle, issues arise within strata corporations in the same way conflicts arise within any other governing entity. It is not uncommon for factions to emerge, for people to distrust and intimidate one another, sue for defamation, file restraining orders, seek proceedings in the Land and Environment Court, or, perhaps more simply, just move out.

Strata title is not a cooperative model of ownership. Each lot is a financial asset, likely affixed to an increasingly expensive mortgage. The Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961 is a specific system for organising space, maintaining buildings, and managing people. The logics and relationships embedded within this system of ownership reflect the modalities of real estate, property and the broader economic rationales that govern contemporary Australian society. But just because strata title ownership is not collective in nature does not mean that the idea of commons cannot extend outside of a building’s predetermined common spaces.

Strata title ownership, much like Torrens title ownership and international borders, is simply a particular way we have decided to organise space and manage relationships between people. Along with formalising the mechanics of shared property ownership, the rules and conventions of the strata title system have come to define a certain way of living together, with an enduring impact on the ways we physically separate our private lives from others.

The strata title system of ownership operates in direct opposition to the imagery and lifestyle of the free-standing home in suburbs. The logics of homeownership, the mortgage, and the desire for private domestic life have been crudely melded together with the lives of others, separated by poorly isolated party walls into a complex system of collective self-governance.

Much like the emergence of strata title ownership in the 1960s and the subsequent building boom, the existing suburbs of Australia’s major cities will once more undergo an intense transformation which will require the replacement of many existing single-family homes with large and very complex multi-title buildings. From this transformation, many more Australians will soon find themselves living in very large buildings and legally bound to a complex entity with complete strangers.

Along with spatial transformations, new ways of living very close together will require simultaneous advancements in ways that the governing entities formalise and manage relationships between people who may not have much in common. What they do have in common for certain is that they live in the same building. Surely that should be enough to consider the possibility that common property is not just the lobby, or the 16-metre double loaded corridor, or wind-swept rooftop BBQ area and pool. Common property is the space where individual lives collide—a space in-common, shared for brief conversations, polite encounters and lives lived together.

-

Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (Leipzig, Otto Wigand, 1845) ↩︎

-

In Australia, A Class 2 building is a multi-unit residential building where people live above, below or next to each other. ↩︎

-

First outlined in the Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961. Act No. 17, Section 4, although the exact distinction varies between different states and territories, and with later changes to the act in 1974 which shifted the line of demarcation to the inside face of the wall dividing instead of the centreline of a wall. ↩︎

-

Specifically outlined in the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015, which accompanies the most recent Strata Schemes Development Act 2015. ↩︎

-

DePaul College of Law, Condominium: An Introduction to the Horizontal Property System, DePaul L. (Chicago, Illinois 1962) Vol. 11, Issue 2, Article 7, p. 322. ↩︎

-

Comparable forms of multi-title ownership also emerged during this time; a German system was legislated in 1951 but was not widely adopted outside of the country, perhaps due to the fact the German word ‘Wohnungseigentumsgesetz’ is very difficult to pronounce. ↩︎

-

A group of apartment buildings located in Salt Lake City, known as “Greystone Pines” is thought to be the first modern condominium built in America. ↩︎

-

Butler-Bowdon, Sydney apartments: the urban, cultural and design identity of the alternative dwelling 1900–2008. (Sydney University Press, 2009) ↩︎

-

HeriCon, Heritage & Architectural Consultants “The Macleay Regis, Conservation Management Strategy” 2011, p. 11. ↩︎

-

Stevens Terrace, at 73 Windmill Street, The Rocks, Sydney is widely considered to be the first purpose-built apartment building in the country, built in 1901 as an upmarket boarding house for merchants. This building contains 11 apartments. It recently sold at auction for over $10 million. ↩︎

-

“What is Company Title and Strata Title?” Taylor and Scott, Last modified 26th of February 2020, taylorandscott.com.au/what-is-company-title-and-strata-title ↩︎

-

This was the most substantial intervention in the housing market. The Commonwealth Savings Bank provided funding and mortgages for the construction of private homes through housing authorities. ↩︎

-

Specifically, the local government act of 1919 and 1921, and the Commonwealth State Housing Agreement (CSHA) 1945. ↩︎

-

Ruth Thompson, Sydney’s Flats: A social and political history (1986). ↩︎

-

Established by the NSW labour government in 1950, the Property Law Revision Committee was comprised of three men, one of whom became the legal counsel of the private consortium. ↩︎

-

Kondos, A. (2016). “The hidden faces of power: A sociological analysis of housing legislation in Australia” in Sherry, C. Strata Title Property Rights: Private Governance of Multi-owned Properties, p. 20. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Estimation based on data from NSW Spatial Exchange and Service NSW. ↩︎

-

The “Randwick General Policy for Control of the Siting, Design and Erection of Residential Flat Buildings 1974” is the predecessor of the NSW Apartment Design Guide. The Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 also emerged after this period of densification and suburban transformation. ↩︎

-

Coincidentally, 1961 was the last year of Sydney’s once-great tram network, which was removed to open up the streets for the private automobile. ↩︎

-

Jimmy Thomson, “Apartment life: new strata report gives lowdown on investors and owner-occupiers” The Australian Federal Review, June 2018 afr.com/wealth/apartment-life-strata-report-gives-lowdown-on-investors-and-owneroccupiers-20180628-h11zs0 ↩︎

-

This does not apply to strata title buildings in the state of Victoria, in which strata title ownership extends to the middle of each party wall and the outside face of external walls. Specific strata-title laws vary slightly in each state. ↩︎

-

Torrens title ownership is a centralised system of ownership which enables the transfer of land titles and registration of ownership through a central state register. It was enacted through the Real Property Act 1858. This system enabled the drawing of lot boundaries and the sale of Australian land to the English landed gentry. ↩︎

-

Hazel Easthope The fourth tier of governance: managing the future of our cities, 2009. ↩︎

-

Hazel Easthope, Bill Randolph and Sarah Judd City, Futures Research Centre, Governing the Compact City: The Role and Effectiveness of Strata Management in Higher Density Residential Development, 2012. ↩︎

-

Cathy Sherry, Strata Title Property Rights: Private Governance of Multi-owned Properties, 2016. (This the preeminent reference book relating to the history and theory of strata-title ownership). ↩︎

-

Gary Nunn, “Shooting pets, spying and no washing on balconies: Australia’s strata wars” October 2019 theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/oct/11/shooting-pets-spying-and-no-washing-on-balconies-australias-strata-wars ↩︎

Kieran Patrick is a graduate of the UTS School of Architecture. Having recently left the institution, he has entered the corporation, working at one of Australia’s largest property development groups in feasibility, acquisitions and design development of multi-residential buildings. He is interested in the relationship between housing supply, urban form, and domestic space.