Learning to Unbuild

Second Edition

Graduating from our postgraduate degrees in the midst of a global pandemic and ecological crisis, we entered an industry unable to resolve its fundamental contradictions. An industry where “sustainability” is at the forefront of professional discourse and yet construction remains one of the largest contributors to the climate crisis. The recent initiative “A Global Moratorium on New Construction” called for the suspension of all new construction as the prime locus of exploitative and extractive capitalism, while demand for architects and builders to participate in Australia’s thriving construction and development sector has never been higher.1 In an attempt to navigate the contradictions presented to us, we began a research-based practice to test how we could design and build with less waste, an architecture based equally on process and aesthetics.

We quickly discovered that designing with and for waste is something that neither our jobs nor our six years of university prepared us for. Not only do we face a complex problem of warranties, liabilities, structural feasibility and compliance concerns, but also assumptions about the junky aesthetics that accompany second-hand building materials. How do we look beyond the superficial application of these types of materials and legitimise their value within professional practice?

In every Second Edition project, we test a particular technique for reducing waste. While not all of them are success stories and most of them are still works in progress, we have learnt a lot. We hope that by sharing some of our experiences with you, deconstruction and reuse amongst designers in Sydney will become more accessible and eventually, an acceptable alternative to the imperatives of exploitation and extraction.

Learning to Unbuild

When we first conceptualised Off-cut Kitchen we had a single goal: design a beautiful kitchen entirely out of waste material. Kitchens are the most common targets of regular renovations, often occurring at an abbreviated life cycle of five to ten years. Many designers think of their designs as timeless; some even list longevity as their approach to sustainability. The reality is that no matter how beautiful or functional a design, trends change. Something that was considered desirable fifteen years ago may not be today. A kitchen designed to one client’s taste and functional requirements may not suit another.

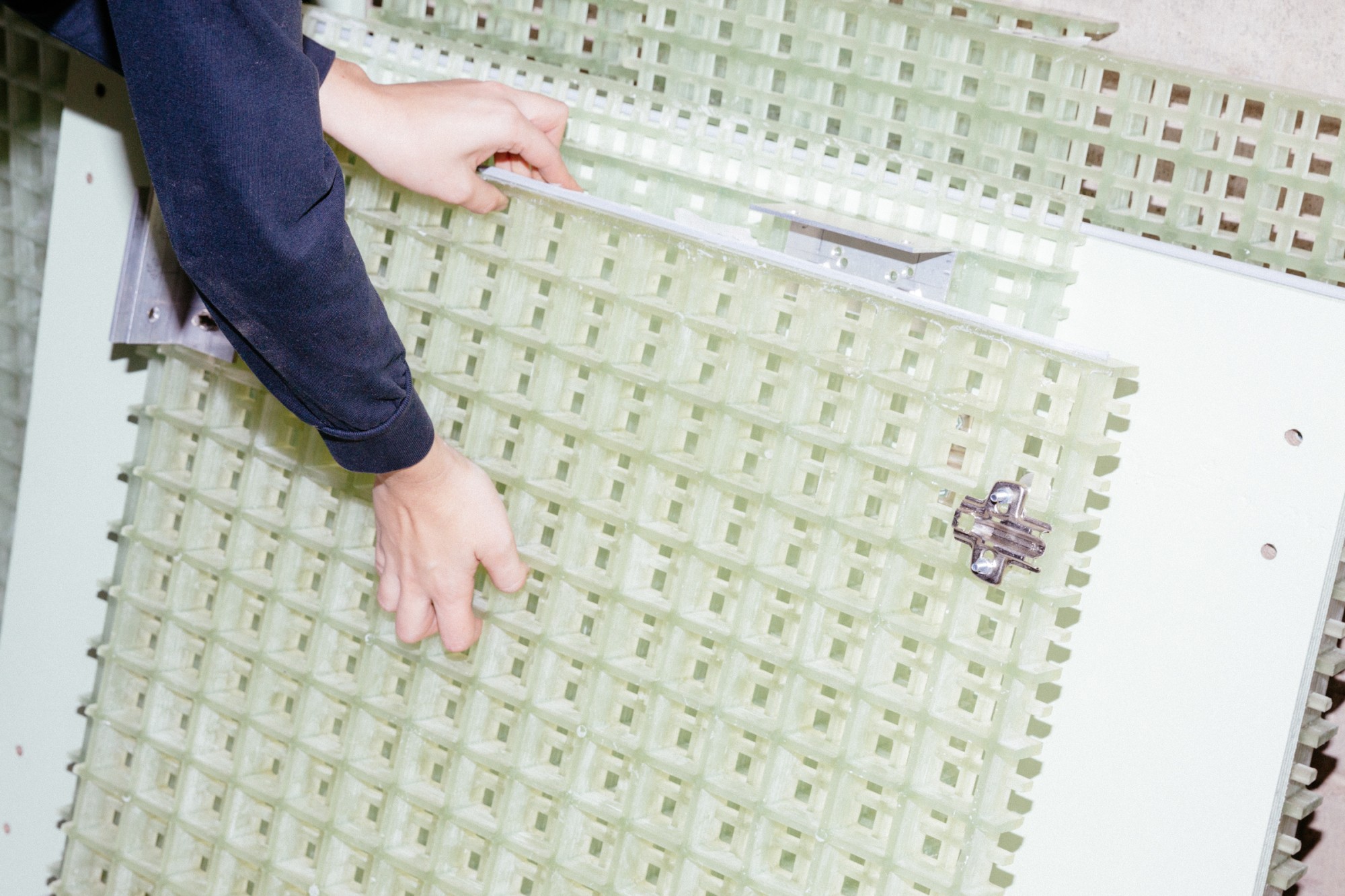

Where conventional design often follows what’s in fashion, our work begins with “following the material.”2 For Off-cut Kitchen, we sourced local, second-hand fibre reinforced polymer (FRP) offcuts most typically used in industrial or outdoor flooring settings. Material choice was a deliberate rebuke of trendy aesthetics in architecture and design. Left raw and uncoated, the FRP appeared pale, almost translucent green. This characteristic then informed the colour of the carcass and the pigment of the terrazzo benchtop fabricated with Natural Brick Company. Aesthetic value is re-prescribed to its lack of carbon heaviness: its locality, availability, and the way that it is designed for.

At this stage we decided to design the kitchen for a fifteen-year life cycle, at the end of which it can be taken apart and reintegrated into a new design. While there are many guides detailing Design for Disassembly (DfD), one of the better ones being The 2005 Acumin Principles, we soon realised that DfD and designing with waste material are at times at odds with one another.3

We designed the kitchen for repeated disassembly and reassembly, working primarily with mechanical fixings and scrap metal angles over bespoke hardware. The refinishing process made these all look like new. DfD guidelines instruct us to design with standard and modular sizing. Off-cuts, however, do not come in standard sizes. In fact, every single offcut is different and each offcut produces its own offcuts. There are trade-offs in every process: specifying new material allows for its efficient use, but working with waste material is imprecise and often messy. Similarly, specifying older technologies may come with shorter life spans and lower performance qualities.

Learning to unbuild defies the idea that design should follow fashion, or even taste in the conventional sense. Rather, it is about building an appreciation for a new kind of aesthetic, where material ecologies are valued more highly and construction tectonics are not hidden or made precious and totally neat, but are driven by disassembly logics. Using offcuts, leftovers and salvaged materials asks us to embrace the misalignments and imperfections involved in the process.

Learning to Under-design

Off-cut Kitchen was an archetypal research project: no clients, no budget, and entirely process-driven. While we learnt a lot about the processes involved, we had not yet had exposure to navigating client needs and expectations. “Following the material” as a design principle is only guaranteed to work for salvaged goods if they are procured prior to a finalised design.4 Often, form might follow something more flexible and ad hoc, like availability.5

This approach presents logistical and financial risks including long-term material storage, double or triple handling of materials, and very little room for design development or client feedback. We have found that procuring materials prior to design sign-off often leaves the client in the dark. Not knowing what they are getting or its definitive budget is an uncertainty many clients are unwilling to risk, and understandably so. In short, there is no easy navigation of risk when designing with waste material.

A concept design for the interior renovation of a rural cottage became a test case in a client-initiated project made entirely out of waste material, prior to final procurement. The first thing we did was set ourselves rules. These included demolishing as little as possible, and where elements were removed, they were to be deconstructed and reintroduced into the design.

The spatial planning of the scheme hinged on carving out a generously-proportioned open space for the living areas. These proportions made the space at once ambiguous and yet full of possibility. The joinery and furniture fitouts were not specified or constrained, left intentionally open to accommodate a multitude of found objects or ones designed from off-cuts.

Salvaged materials were reconstituted as new assemblages and, as we had not yet procured additional materials, new additions were assigned a simple palette. The finishes were designed to be adaptable to multiple material selections. For example, the internal walls were presented as generic 900x1200mm white panels, allowing us freedom to choose materials based on what will be available at the time of construction.

Designers are trained to design and specify everything; the cottage was a process of unlearning over-documentation and learning to allow for ambiguity. It demanded we make space for continuing the design process through construction stages—a risky process not necessarily suited to every client-architect relationship, but one that defines our intentions from the get-go. It also means that detailing must be done in a way that accommodates the temporality and availability of materials, and is tolerant of future change. Rather than placing value in a static aesthetic or tectonic outcome, ambiguity allows for value to be placed in the process.

Learning to Procure

One of the questions that arises in most conversations with designers is where to find salvaged construction materials. Salvage yards still exist, and are great for materials such as timbers or heritage fixtures and fittings. However, due to space limitations, there are few that remain in operation. Using the social networks and online marketplaces already at hand opens up a new stream of grassroots procurement. Materials and objects can be bought and sold directly from one consumer to another, reducing the excess transport and storage typical in the commercial sector.

These online marketplaces are overlooked in the profession as a legitimate source of procurement, so we tested its viability in a collaboration with another architect for the interiors of two bathrooms. We challenged ourselves collectively to procure all the fixtures and finishes from online second-hand marketplaces. In total there were 30 items to procure: four types of tiles, two joinery units, 20 sanitary fixtures, two stone benchtops and two timber shelves.

Trawling through the pages of Gumtree and Facebook Marketplace, it becomes apparent what the current trends in bathroom ware are, as well as the stalwarts like brushed metals and stainless steel. Designing to commonality was key. One of the greatest challenges was developing an efficient and manageable approval process with the client. Without a bricks-and-mortar store to see, touch and test fixtures and finishes, we were asking for the client’s total trust. Despite using a range of conventional visual guides like reference images, mood boards and inspections where possible, achieving client buy-in required an adjustment to the typical consumer mentality. Instead of 20 tap styles and finishes to select from, there were two; instead of 40 different tile colours and finishes, there were five. While this made the process easier at times, it required a higher degree of flexibility from the client and a willingness to adapt style and personal preference to what was available.

An unexpected barrier throughout our practice designing with salvaged materials is the varying appetite fabricators have to work with waste. There are many fabricators that sell their off-cuts and even ones that give them away for free. However, finding people that are willing to fabricate with offcuts proves more difficult. Learning to procure is not just about finding the right finishes to satisfy an aesthetic goal, but also about procuring the right services and labour to carry it out. We are no experts when it comes to specific trades. We have come to view our practice as one that fundamentally relies upon expert technicians and collaborative processes.

Learning to procure when dealing in waste and second-hand material is about being sensitive to our working relationships with people. It forces us to become more familiar with our local communities and the material that makes up our neighbourhoods. To find the right person to work with waste, we have to get to know many more. It is about being able to effectively communicate with the people we work with, mutually undergoing the difficult process of mediating existing aesthetic sensibilities with a new ethics. It is a process not only characterised by a set of limitations, but as a field of many potentials.

Each of these projects has been a testing ground for a new way of thinking about and working within architecture. By isolating unknown factors to a specific part of the project—a bathroom or a kitchen or even a chair—we are able to test different processes and methods in direct and manageable ways. Our goal is to accumulate enough experience to be able to apply these strategies throughout a project.

We have seen a dramatic increase in construction costs over the past twelve months due to imminent resource depletion, coupled with a global pandemic impacting material availability and supply chains. Key building materials such as steel, insulation, and timber have respectively increased in price by 10%, 20%, and 25%—with reports of sharper increases within areas of high construction activity, such as Sydney.

The global supply deficit makes urgent the growing need for widespread specification and reuse of locally acquired, salvaged and second-hand building materials. Out of necessity, we are active in our attempts to shift how material itself is valued, an Atlas-sized boulder pushed inch by inch. We think of it in embodied terms: not just by how much carbon it took to make a material, but also by how much life it has yet to live. These potential lives that are often under-looked define our practice and we hope that it comes to define many more.

-

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, A Global Moratorium on New Construction (2020) ↩︎

-

Helene Frichot, Dirty Theory: Troubling Architecture (Germany: AADR, 2019) ↩︎

-

Philip Crowther, Design for Disassembly – Themes and Principles (RAIA/BDP Environment Design Guide, 2005) ↩︎

-

Helene Frichot, Dirty Theory: Troubling Architecture (Germany: AADR, 2019) ↩︎

-

Taleen Astrid Josefsson and Liane Thuvander, Form follows availability: The reuse revolution (IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2020) ↩︎

Second Edition (Shahar Cohen and Amy Seo) is a research-based practice exploring deconstruction and reuse within the built environment through consultancy, material experimentation, prototyping and knowledge sharing. We advocate for practical, local and feasible solutions with real-world applications.