Built by the Book

Dr. Emma Letizia Jones

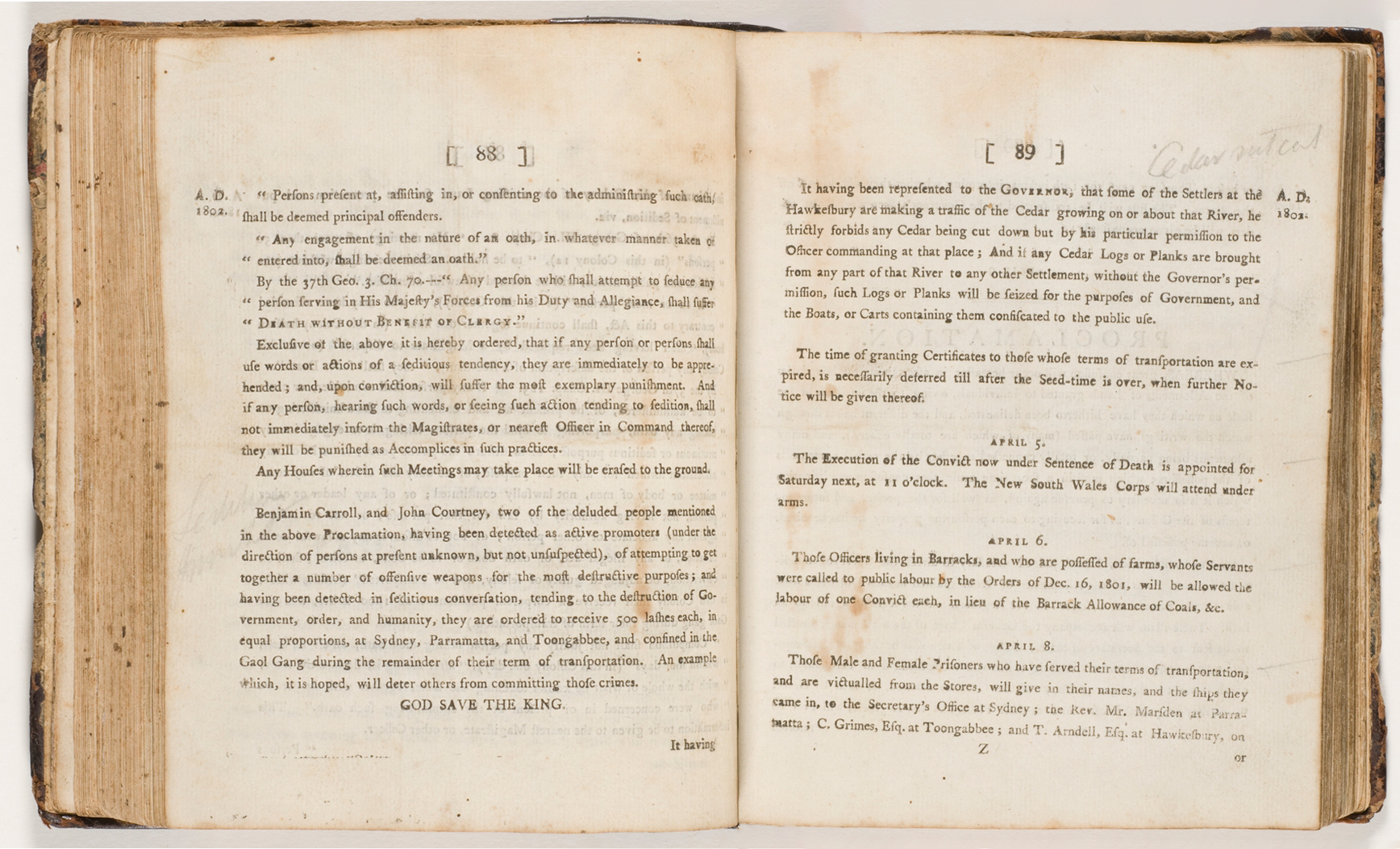

The New South Wales General Standing Orders was the first book ever published in Australia, appearing in New South Wales in 1802. A compilation of government orders laying down the rule of English law in the penal colony, it was, paradoxically, printed by a former convict: the pioneering Australian publisher George Howe, on a small wooden printing press brought from England with the First Fleet in 1788. Dealing with such matters as how many rations of flour, tea and other basics settlers were to receive, as well as setting out the various punishments for cow rustling, public drunkenness and other offences, the concise publication was a sort of DIY manual for running a colony: the foundational document of a so-called civilisation.

The only area into which the standing orders seemingly did not intervene was the question of how the colony should be built. Indeed, there was precious little written advice in this area, and those with any ambition for building had to rely on the rule books of Britain. When Governor Macquarie arrived to take up his post in New South Wales in 1809, his wife, Elizabeth Macquarie, transported with them a library of English architectural advice books, including E Gyfford’s Designs for Elegant Cottages and Small Villas (1806), Gyfford’s Designs for Small Picturesque Cottages and Hunting Boxes (1807), and the second edition of William Chambers’ A Treatise on the Decorative Part of Civil Architecture (1791). The role of these books is complex. Though they undoubtedly represented usurping English building narratives and traditions, they were also used by the Macquaries as a form of resistance to colonial rule, as they enabled the development of local infrastructure that allowed Sydney to extract itself from British mandates and establish its own identity. They are therefore tools of colonial violence, and tools against colonial violence. As documents, these DIY building manuals encapsulate the painful paradoxes of Australia’s urban histories. But of these three titles, only the Chambers could claim to belong to the genre of “architectural treatise.” The others were more in the vein of “pattern books”: books which presented a smorgasbord of plans and elevations for suggested building types in various guises and styles meant for copying by the amateur or client-builder, from country houses and farm buildings to follies and townhouse terraces, from classical to gothic, baronial to Italianate rustic. A kit-of-parts that in turn formed part of a whole family of more pedestrian building publications that also included the building manual, the builders’ price guide, and from the nineteenth century onward, the trade catalogue.

In art historical terms, a book like Chambers’ architectural treatise has always occupied the highest rung of architectural advice books, while building publications have largely been excluded from the formation of canonical discourses. However, their ubiquity defies (or perhaps confirms) their “lower” status. In 1899, for example, Scottish plasterer William Millar published his building manual Plastering Plain and Decorative. Partly a “how-to”’ guide for client-builders and craftsmen, and partly a history of architecture through the lens of the plastering tradition, Plastering has since become one of the most commercially successful architectural advice books of all time. Now on its 10th edition, its last reprinting was in 2010. It is regularly used in contemporary heritage restorations of Victorian houses and public buildings in Australia, not least because it provides patterns, techniques and plaster recipes no longer in common use, but necessary for craftsmen and builders to master in order to replicate or repair existing building details more than 100 years old.

Despite its ubiquity, Millar’s manual belongs to that vast family of building publications that have largely been excluded from the canon of European-origin architectural literature and its historiographies. Architectural history has instead been established upon other forms of literature—namely the architectural treatise—reflecting the architect’s operation from within a scholarly western tradition rooted in the study and reinterpretation of classical antiquity, with the goal of establishing universal architectural norms and ideals.1 Conversely, the building manual, pattern book or trade catalogue has typically been examined as a derivative abridgment and “practical” aberration of the academically elevated discourse produced by these treatises. But what would it mean to re-evaluate the significant forms of knowledge produced by building manuals and related “how-to” documents: trade catalogues, pattern books, building guides and periodicals, builders’ manuscripts, notebooks and price books? These offer an alternative history of architecture outside its established canons, but they also reframe Australia’s architectural history as one intimately connected to the printed word: often not as set down by classically educated architects but by craftsmen, self-taught amateurs, tradespeople or companies, and occasionally, women.

Trade catalogues, in particular, were essential to the development of Australia’s nineteenth-century building stock. The first catalogues emerged in the 1770s in Britain, and were associated with the west-Midlands and Sheffield metal trades.2 Yet they soon became popular advertising tools for all kinds of building trades, particularly those associated with prefabrication: a mode of manufacture new to the nineteenth century that lent itself well to the catalogue format. George Jackson and Sons was one such company making early use of catalogues to sell prefabricated ornamental features (as opposed to work done in-situ) around the world, including to Australia. The London company released their first major self-published trade catalogue in 1836: a 32-plate engraved set of prefabricated interior ornament designs in plaster and papier mâché. The catalogues were issued in a mail-order system, which was also used to facilitate sales abroad. The result was that trade catalogues spread libraries, and eventually exports, of standardised ornament on a global scale. William Millar himself confirmed that trade catalogues were explicitly intended for serving the export business. In the case of the fibrous plaster advertised in the Jacksons’ catalogues, he asserted that it was “light and tough” as well as cheap, and therefore “sent abroad in large quantities to our own colonies and other countries.”3 These documents were circulated more widely than any architectural or building literature before them, and although in their countries of origin they may have been viewed as third-tier literature, in the distant locations to which they travelled they became germinal documents for emerging local architectural identities, and have been faithfully and carefully preserved as such.4

Catalogues by George Jackson and Sons, along with the occasional discovery of the exported ornaments themselves, have, for example, been found scattered throughout the United States, Australia and Canada. In 19th century Australia, they replaced a shortage of both skills and materials in the local building trades. Until (and for many years after) gypsum deposits were discovered in Victoria and New South Wales in the 1860s, architectural details were ordered from these catalogues and sent from Europe and the UK. They were then affixed by local, often unskilled craftsmen. On the strength of a showing at the London Great Exhibition of 1851, George Jackson secured an important Australian client: Thomas Mort, who commissioned them in 1856-57 to provide mouldings for his home “Greenoakes” in Sydney, designed by Edmund Blacket.5 Since 1859, at least one identified set of papier maché cornices purchased from a George Jackson and Sons catalogue has been installed in the drawing room at the “Woolmers” country house in Tasmania, but many more may have gone undocumented.6

Occasionally, catalogues were used in Australia to order entire portable building systems, to be shipped in parts and reassembled (according to instructions) in the final locations. Australia (and particularly Victoria) holds the world’s largest surviving collection of portable timber and iron buildings, including villas, churches and public buildings. Many of these were manufactured in Singapore and Hong Kong, bearing markings in Chinese characters—a testament to the already global movements of the building trade, even by the mid-nineteenth-century.7 The catalogues that advertised these buildings include Charles Bielefeld’s Portable buildings designed and built by Charles F. Bielefeld, patentee (London: C. F. Bielefeld, 1853), and Charles D. Young’s Illustrations of Iron Structures, for Home and Abroad (Edinburgh, 1855) and Description (with illustrations) of Iron and Wire Fences, Gates, et, etc, adapted especially for Australia (London, 1850).

Contemporary Australia, through the brutal and near-improbable circumstances of its foundation and formation, has always been a country built on the back of DIY. After the early Standing Orders came the price books, the pattern books, the manuals and the trade catalogues that proliferated in the 19th century, and different forms of these books continued to be produced in new forms well into the 20th. One of the most famous 20th-century examples in architectural circles might be Walter Bunning’s Homes in the Sun (1945), an Australian modernist take on the old English pattern book in the E Gyfford vein, though this time with house plans calibrated to the Australian climate. The contemporary hardware store catalogue (e.g. Bunnings) may also be considered a direct descendant of George Jackson and Sons’ offerings. Such publications, unlike the academic treatises of the eighteenth century, shirk elitism in their appeal to the average Australian to “get things done.” Australian architects tend to ridicule and denigrate this unskilled Australian builder: a hapless DIY amateur, building by the book and ordering from the catalogue. And yet it is this figure, and not the architect, who is responsible for the majority of our built environments, and who, if tasked to improve them, given the climate and emissions problems Australian cities are facing, will surely need the right tools to do so. What, then, would these DIY tools look like? Could they take the form of contemporary building guides, learning from the best examples of the 19th century building books of old? What advice would they offer? How would they be designed? In our current climate, might they eschew new construction altogether, and advocate and explain only the principles of repair, care, reuse? Here is a radical proposition: if architects were to stop building new altogether, turn their minds to producing books instead of luxury houses and—yes—embrace the egalitarianism of DIY, might they begin to make a more convincing case for their continuing relevance to society?

-

The architectural treatise in Europe operates from the Renaissance onwards within the Albertian context. The foundational model is Giovanni Battista Alberti’s De Re Aedificatoria (‘On the Art of Building in Ten Books’) of 1452, which is a reinterpretation of the only surviving text on architecture from classical antiquity by Vitruvius. Alberti’s treatise aimed to codify a classical language of architecture, establishing stylistic norms and theoretical principles on which the practice of architecture could be founded. For a clear characterisation of the architectural treatise of the Renaissance and its legacy see Payne (1999), Hart (1998) and the exhibition catalogue produced by Waters and Brothers (2011). ↩︎

-

Susan Lambert, ed., Pattern and Design: Designs for the Decorative Arts 1480—1980, catalogue of an exhibition held at the Victoria and Albert Museum March 23—July 3, 1983 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983), 24. ↩︎

-

William Millar, Plastering Plain and Decorative (London: B. T. Batsford, 1899), 343–345. ↩︎

-

It is far more in their adopted countries than in their countries of origin that trade catalogues have been conserved, digitised and cared for as important architectural documents. Two such catalogues, found in Australia and Canada, have been digitised and are available to view online, in the collection Sydney Living Museums: Part of the collection of relievo decorations as executed in papier mache & carton pierre (London: George Jackson and Sons, 1849). Available online; and in the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture: Examples of a few architectural ornaments, &c. : manufactured in fibrous plaster, carton pierre, and wood (London: George Jackson and Sons, 1902). Available online. ↩︎

-

London, Great Exhibition, 1851, Catalogue, Sect. III. Class 26., 730. ↩︎

-

See Clive Lucas, Australian Country Houses: Homesteads, Farmsteads and Rural Retreats [Sydney 1987], 146. ↩︎

-

See: Miles Lewis, “The Asian Trade in Portable Buildings”, Fabrications, 4:1 (1993): 31-55, DOI: 10.1080/10331867.1993.10525060; Miles Lewis, “The Diagnosis of Prefabricated Buildings,” Australian Historical Archaeology, 3 (1985): 56-69. Available online. ↩︎

Dr. Emma Letizia Jones teaches design and the history and theory of architecture at HKU. She is an Italian-Australian architectural historian researching the translations occurring between architecture and its drawn and printed representations, particularly in early nineteenth century Berlin and London during momentous transformations in the printing and building trades; and the relationship between books and buildings in globalised architectural culture during the eighteenth and nineteenth century.